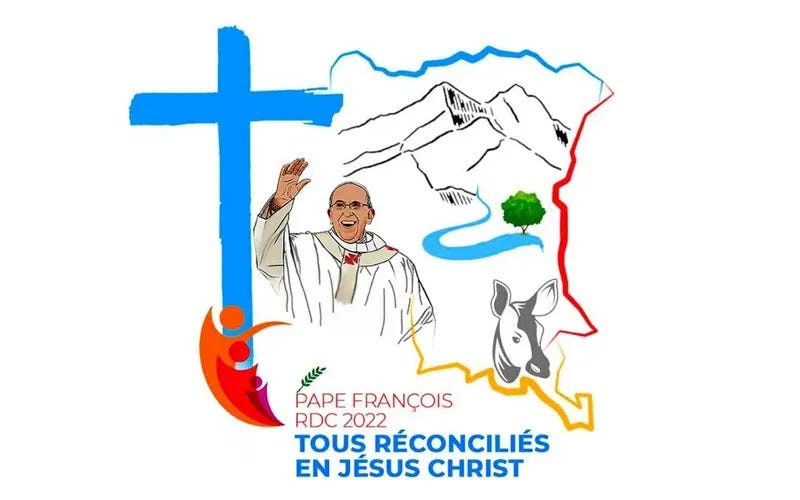

Pope Francis sets out on a trip to the Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Sudan on Tuesday.

The visit was expected to take place in July 2022, but was postponed due to the 86 year-old pope’s health problems.

Local Catholics have high hopes for the journey. But how reasonable are expectations for the trip? Can local Catholics hope for more than some words of consolation and appeals for peace, or will the pope’s pleas be ignored by political and military leaders?

From state ally to critic

The case for pessimism is easily made. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has been plagued by corruption, mismanagement, and seemingly endless conflicts for decades. Two visits by Pope John Paul II did little or nothing to stem the downward spiral.

But Fr. Godefroid Mombula, a Congolese missionary and academic based in Kinshasa, noted that there were important differences this time.

“Back then the country was a totalitarian dictatorship, run by President Mobutu,” he told The Pillar, referring to the authoritarian leader who ruled the nation from 1965 to 1997.

“The situation has since changed; we have a multiparty system. Now, the main risk is Balkanization and the war in the east. I understand the pessimism; development has not yet taken off. Nevertheless, small changes are noticeable.”

The existence of a multiparty system points to the Church’s considerable influence within the country — the governing transition from a dictatorship was overseen by the late Cardinal Laurent Monsegwo. And amid the chaos of ensuing years, the Catholic Church, which claims the allegiance of just over half of the country’s 70 million people, has been the only institution to see its credibility remain intact, or even rise.

“The Catholic Church was always a key player, starting in colonial times, when the Congo was the property of King Leopold II,” said Fr. Mombula. “The king could not rely on the Belgian administration to run the country, so he outsourced the day-to-day administration to different Catholic congregations. This gave the Church a political clout that it doesn’t have in many other countries.”

“Step by step, the Church distanced itself from the state. Formerly a reliable ally, it has increasingly become the state’s strongest institutional critic,” said the priest, who pointed out that the Church runs a vast network of social institutions, ranging from schools to hospitals.

In 2018, the Church encouraged demonstrations against the regime led by Joseph Kabila, provoking a crackdown by government forces in which dozens of people were killed. The pressure, however, led to the first peaceful transition of power in the country’s history.

Fr. Mombula expects the pope to speak of the need for peace, warn leaders against corruption, and call out multinational corporations that exploit the DRC’s vast natural resources, fuelling ongoing conflicts and leaving the population in dire poverty.

But the trip’s biggest effect could be to fortify the local bishops in their ongoing struggle to hold the political class accountable and promote serious reforms, which they hope would pave the way for establishing lasting peace in the country.

📰

War and macadamia nuts

The original schedule for Pope Francis’ trip in 2022 included a visit to Goma, one of the main cities in the east, the region where the worst fighting is taking place. At least 70 armed groups are battling the government and each other, spreading violence that has led to the displacement of more than 1.6 million people.

At an online conference, organized by international charity Aid to the Church in Need (ACN) held on January 16, Fr. Mombula smiled as he said: “What we know from the official media is that the pope will not be going to Goma for health reasons.”

But he added, “There are things we don’t say, but they are there,” implying it is really the security situation that is preventing the pope from visiting the city.

A group of war victims is expected to be flown in from the east to the capital, Kinshasa, to meet with Pope Francis. But the local population is bound to be disappointed, said an international aid worker who knows the region well but asked not to be identified as they weren’t authorized to speak publicly.

“Pope Francis has always shown an interest in visiting parts of the world deeply affected by conflict, where there is so much suffering. Eastern Congo is one such place, it has been racked for decades by seemingly endless conflict,” the aid worker said.

“The people feel abandoned by their leaders and by the world in general, and by canceling this part of the pope’s trip I feel that this feeling will only intensify. These people have a unique resilience, and they well deserve to be visited by somebody who says he cares about them and feels their pain.”

The aid worker added: “As my mission there ended, people kept asking me: ‘Will you tell people in your country about what is happening here?’ I could still see some hope in their eyes. But a decade later, when I returned, I saw that this hope had faded, and it is harder to find nowadays.”

Could the pope’s visit to the DRC make a lasting difference?

“Above all, it would provide comfort to a population that has suffered so much, and call the attention of the world to this region,” the aid worker said. “I remember when Francis visited the Central African Republic a ceasefire was negotiated for his trip. This ended up lasting several months and it allowed the people to go back to a life of normality, at least for some time. Perhaps the same could happen in Goma. But that could just be wishful thinking.”

When speaking of possible positive effects of the DRC trip, Fr. Mombula cautioned against expecting immediate results.

“Let us learn from the macadamia nut tree,” he said. “When cultivated, the first year the tree looks like it won’t live; the second year it really looks terrible; and the third year it looks like it should be dug up and burned. The fourth and fifth years are not much better. But the sixth year, the tree begins bearing fruit, and it continues to bear fruit for up to 100 years.”

What’s different about South Sudan

Outsiders might dismiss both the DRC and South Sudan as failed states, but the countries’ circumstances are quite different.

South Sudan is the world’s youngest country, having gained independence from Sudan in 2011. While Christianity has deep roots in the DRC, which has a well-established hierarchy and even its own Zairean Rite, the Catholic faith in South Sudan is less firmly rooted, people familiar with the region told The Pillar.

Felipe Ribeiro, a Canadian-born Catholic who has lived in both countries while working for a private contracting company, said: “The two are comparable insofar as the Church is a very influential institution, socially, and widely respected. If you attend a Mass, you will see that it is the highlight of people’s weeks, and that their faith is central to their lives.”

“However, you can see that the Church in the DRC is more mature. In South Sudan, the Church is very much the result of hard work of brave missionaries who risked their lives to take the faith and the sacraments to a people who lived through decades of war.”

He added: “Both countries still have a strong sense of reverence for clergy. Priests are often called upon to mediate internal disputes and avoid conflict escalation, and even at a national level, bishops have a lot of political clout and are also called on to mediate conflicts and intervene at a grassroots level to promote peace.”

📰

Another thing both countries have in common is a problem with tribalism. Sr. Beta Almendra, a Portuguese missionary stationed in Wau, the country’s second-largest city, explained that tribal loyalties still trump religious convictions in South Sudan.

“If war were to return, tribalism would prevail,” she said. “Christianity is much less relevant. Churches are full of children, and whenever the bishop visits a community, hundreds of youth turn up to be confirmed, but there are not that many adults. When it comes to church marriages, for example, we have maybe one or two a year.”

Tribalism is a major obstacle in many African countries, but in South Sudan, it tore the social fabric apart after independence and has slowed the peace process.

Fr. Abe Samuel, who is coordinating the papal visit to the capital, Juba, blamed politicians.

“In the years when we were fighting for independence, we were very close and we didn’t allow problems to divide us,” he said, speaking at the ACN online conference.

“Tribalism came about when we became independent. Politicians are the ones who incite people to hate opposing ethnic groups. If the politicians could refrain from causing inter-tribal strife in the villages, then we can have peace.”

Speaking to The Pillar, Bishop Christian Carlassare, head of South Sudan’s Rumbek diocese, seconded this.

“Belonging to an ethnic group is important, but it does not have to become a question of tribalism,” he said. “A tree is strong because of its roots, but it is also beautiful when it has branches ready to intertwine with other trees and widen its shade. People of South Sudan know how to live together. Leaders have used ethnicity to manipulate people and keep them under their control.”

The pope is expected to address this issue in his speeches.

A shocking gesture

Pope Francis regularly makes appeals for peace in conflict-ridden parts of the world. But by any standard, the attention he has paid to South Sudan is special — and it led to one of the most surprising gestures of his papacy.

It’s important to understand the gesture’s background. When the territory of South Sudan was a colony, the British carved it into spheres of influence which they divided between different churches, hoping to avoid tensions. Catholics, Anglicans, and members of the Church of Scotland (Scotland’s national church) all play an important role today and have been united in their efforts to promote peace.

Fr. José Vieira, a Portuguese Comboni missionary who spent years in South Sudan and is now in neighboring Ethiopia, pointed out that the Anglican and Catholic archbishops of Juba coordinate their travels so that the capital city is never left without a chief shepherd.

In 2019, at the suggestion of Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, South Sudan’s top political leaders traveled to the Vatican for a spiritual retreat to encourage peace-making efforts. At the end of the retreat, Pope Francis stooped — with considerable effort — and kissed their feet, leaving them perplexed.

Fr. Vieira remembers the moment well.

“Pope Francis left me stunned when he knelt to kiss their feet,” he recalled. “They were also clearly shocked with this prophetic and humble gesture of peace and reconciliation, to bend down and kiss the blood-stained feet of the warlords who have held the state hostage since 2005.”

The practical results of the gesture, however, are more difficult to gauge.

“It had zero impact on the leaders,” said the Comboni missionary. “They continue to fight for their own economic interests, without a shred of concern for the victims.”

Fr. Vieira suggested that the only solution was to remove the current leadership and replace it with fresh faces taken from South Sudan’s large diaspora in countries such as Australia, the U.K., the U.S., and Canada.

Sr. Beta agreed that a new generation of leaders was necessary, but expressed optimism about the prospects of lasting peace.

“Some say that the president did not return to fighting because of the pope’s symbolic gesture. It continues to leave a deep mark on the politicians and could move them to sit and talk,” she said.

Waiting for a miracle

Bishop Carlassare had first-hand experience of the violence in South Sudan when gunmen broke into his house and shot him in both legs shortly after his appointment as Bishop of Rumbek in 2021.

The Italian Comboni missionary, who has since recovered from his wounds and was ordained a bishop in March 2022, said that the visit was important, but the immediate results were not in Francis’ hands.

“Pope Francis comes as a pilgrim of peace. He cannot make the country anew, but his coming makes a difference,” he said. “He challenges all of us to join him in praying for peace and work for reconciliation. His coming also renews the commitment of the Church to justice and peace.”

Trip coordinator Fr. Samuel ended his talk at the ACN conference by saying that “when the pope touches the ground of South Sudan many miracles can happen.”

“We believe that the message he will bring will be a follow-up to the one he gave leaders in the Vatican, and we hope it will encourage our people to live as brothers and sisters,” he said. “At the moment, as our country is implementing the peace agreement, there are signs things are changing for the better.”

Asked by The Pillar to expand on what Fr. Samuel meant, he said: “The pope’s presence in South Sudan brings blessings and his encouraging words will change hearts to work and promote peace in the country.”

“This is the miracle I was talking about.”