Barcelona’s uneasy relationship with its Catholic past

The mere suggestion of changing a city square’s name has created a stir.

Plaça d’Urquinaona has a major metro station, as well as serving as a hub for buses, cars, motorbikes, and the red Bicing bike sharing bikes that are a regular sight on Barcelona’s streets.

A few minutes’ walk from Passeig de Gràcia, a main avenue adorned with Gaudí masterpieces, and Plaça Catalunya, a 12-acre square generally considered the city’s center, Plaça d’Urquinaona takes its name from the influential 19th-century Bishop José María Urquinaona, who led the Barcelona diocese from 1878 until he died in 1883.

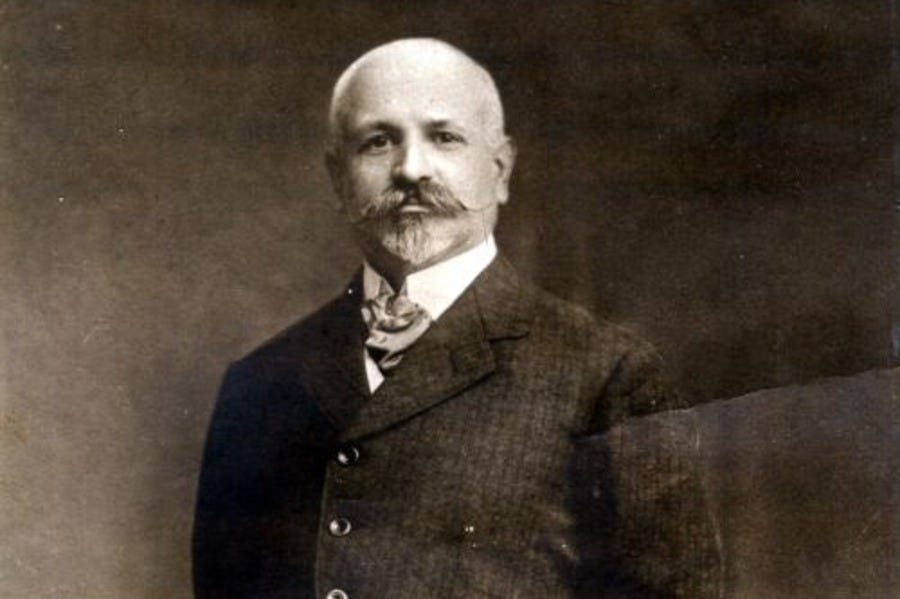

But in recent weeks, posters have appeared on Plaça d’Urquinaona, demanding that it be renamed after Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia, a Catalan anarchist and Freemason who was executed in the early 20th century for participating in a civil uprising. The square was temporarily named after Ferrer during the Civil War of the 1930s.

Soon after the posters appeared to suggest the square’s new name, Spanish media published reports highlighting the campaign.

The Catholic newspaper El Debate reported that the Together for Catalonia party was supporting the proposed change — a surprising move given that, while it supports pro-Catalan independence, it is generally considered a conservative outlet.

Together for Catalonia did not respond to a request for comment.

A petition appeared online, organized by the Observatory for Religious Freedom and Freedom of Conscience, opposing the proposed change.

Pointing to other changes in the city’s public spaces that have removed references to saints, religion, and the Church, the petition lamented that “all of this has a radical secularist objective that seeks to eliminate religion, especially Christianity, from the public sphere.”

The office of Barcelona’s Mayor Jaume Collboni told The Pillar there was “no news about a change of name for Plaça d’Urquinaona” and “no one has brought it up recently.”

Yet the mere suggestion of changing the square’s name has created a stir, and that is because of the city’s complex history with Catholicism – both recently and in the more distant past.

Who was Ferrer i Guàrdia?

Ferrer was a well-known figure in Spain who in 1901 established the Modern School, a secular and rationalist educational project conceived as an alternative to Church-administered education in Spain. The project spread internationally across Europe, cementing his position as an activist of the left.

His fame — or infamy — increased because of the circumstances of his death. He was accused of being involved in the disorder of the Tragic Week in 1909, which was marked by violent clashes in Barcelona between the Spanish army, and a collection of anarchists, socialists, republicans, and Freemasons.

The government convened a military court, convicted him as a ring-leader, though this charge is disputed by his supporters, and sentenced him to death.

“He was shot almost right away,” Enric Ucelay-Da Cal, a contemporary historian who specializes in Catalan history, told The Pillar.

“He may have been involved in the Tragic Week, and its disorganization and its process, or he may not have been. Left historiography will say ‘no.’ Right historiography will say ‘yes,’” he said.

“So he became a hero, to a strong left tradition linked to the Latin line of Freemasonry.”

In 1987, the Ferrer i Guàrdia Foundation was established, and there is a statue of the man in Montjuïc, a hill in Barcelona.

According to Ucelay-Da Cal, the foundation “is small, but is basically a cluster of classic freemason opinion, as opposed to more modern freemason opinion.”

Freemasonry in Latin countries, according to the historian, brings together “Catholic atheists” who have the notion “that salvation is in the church, except they have a different church.”

Through that lens, Ferrer is sometimes framed as a secular saint of sorts, so to rename the square after him would be at best pointed, and at worst deliberately provocative.

Javier Arjona García-Borreguero, a history professor at Francisco de Victoria University, told The Pillar that the proposal to change the square’s name can be understood by the fact that “anticlericalism remains latent in Catalonia today.”

An uneasy tension

Bishop Urquinaona was by no means anti-Catalan. He did many things during his brief stint as Bishop of Barcelona that endeared him to advocates of Catalan nationalism — which at that time, according to Ucelay-Da Cal, was “just love of language and anything Catalan.”

First, he helped to establish a new seminary in Barcelona.

Second, he earned himself the approval of Catalan workers by travelling to Madrid and arguing against free trade policies, thus protecting Catalan textile industries and the broader industrial health of the city.

Third, he played a pivotal role in the naming of the Virgin of Montserrat as the Patroness of Catalonia.

Fourth, he laid the first stone of Barcelona’s celebrated Sagrada Família basilica.

According to Arjona, he is “not a plausible target for accusations of anti-Catalanism that might justify changing the name of the square.”

So why target him? Ucelay-Da Cal suggested there were a few reasons, some practical and others political.

He suggested that “no one remembers who he [Urquinaona] is”, and that Catalans struggle to pronounce his surname — “Urr-key-nah-OH-nah.”. The bishop “is easy to pick on,” he said.

The other reasons are more political in nature.

While the mayor’s office indicated it had no information on the name change, Ucelay-Da Cal suggested that Mayor Collboni would use the square’s name as a political “cheap shot” to bolster his ailing career, because “he has to try and do things that attract specific left-wing bases.”

Recent issues

A big reason why this seemingly grassroots campaign has generated such fear is because of the secular credentials of Mayor Collboni, who came into office in 2023.

During the Christmas festivities for 2025, for the second year running, Barcelona’s city council broke with the tradition of having a Nativity scene outside of the city hall, in Plaça Sant Jaume, in the city’s Gothic quarter. Instead, the Nativity was inside City Hall.

In the buildup to the municipal celebrations for the city’s patron saint, Our Lady of Mercy, in 2024, Collboni also came under fire as references to an official Mass briefly showed up on city council posters and websites via a “technical error,” and then were removed.

The Mass was removed from the official celebrations in 2015, and Collboni’s political rivals have criticized him for not reinstating it. Posters for the festivities in 2025 were sharply criticized by the Barcelona archdiocese for ridiculing the Virgin Mary.

There have been other controversial moves, such as the changing of a street named after St. Mary Magdalene to “Carrer de Magdalena E. Blanc.”

When news filtered out that the name of Plaça d’Urquinaona could be changed, Catholics and conservatives in the city immediately thought the worst.

Echoes across Spain

Debates about the role of public displays of Christianity are nothing new in Spain. In recent days, two big stories have emerged drawing focus on the topic.

The Valle de Cuelgamuros, formerly known as the Valley of the Fallen, hit headlines again thanks to off-the-record comments by Madrid’s Cardinal José Cobo Cano that were leaked to the InfoVaticana website.

The Foundation of Christian Lawyers has filed an administrative appeal with the National Court against the agreements reached between Cardinal Cobo and Minister of the Presidency, Félix Bolaños to “redefine” the monument. Among other things, it alleges the agreements were “signed by an ecclesiastical authority without the competence to do so.”

This has reopened the debate about the future of the monument, which has the world’s biggest cross.

In the second case, following a train crash in January in Adamuz that left 46 dead and 292 injured, the government proposed a “secular tribute” to the victims.

This was rejected by victims’ families on two grounds: they didn’t want to associate with the government due to anger over the circumstances of their relatives’ deaths, and some of them didn’t like the idea of a “secular” tribute.

Many were from Huelva, a town in southern Spain that has high levels of religiosity. One of the sisters of the victims said: “Huelva is Marian territory.”

In the end, there was a Mass in Huelva officiated by the local bishop.

A dispute also broke out over the plans by the president of the Community of Madrid, Isabel Díaz Ayuso, to hold a Mass in honour of the victims in the capital. One of the two trains that collided was travelling to Madrid, hence why the Mass was proposed.

The writer and philosopher Irene Lozano, best known for helping current Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez write his book “Manual de Resistencia,” criticized Ayuso’s proposal as “a blatant appropriation” and suggested a Mass was inappropriate because “there will be agnostics, atheists, Catholics, and Muslims” among the victims.

“I believe that the secular, non-denominational state in which we live should not interfere with people’s religious beliefs,” Lozano said.

And further afield

Spain is not the only country having such debates.

In Greece, a case has recently gone to the European Court of Human Rights about Christian symbols in Greek courtrooms. Two atheists requested the removal of Christian icons in Greek courtrooms during hearings involving religious matters, arguing the icons compromised judicial objectivity, were discriminatory, and violated their rights to a fair trial and to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion.

In November 2025, the U.K.’s Supreme Court ruled that the way religious education was being taught in Northern Ireland, with a heavy emphasis on Christianity, was unlawful.

In Italy, there has been a long-running battle, both public and legal, about crucifixes being hung in classrooms.

Should Catholics in Barcelona see the potential change of the square’s name as part of an international attempt to erode Christianity from public places? Or is it the inevitable result of declining faith in a former Catholic stronghold?

Ucelay-Da Cal, a baptized Catholic who described himself as “by no means a believer,” said it was a bit of both.

Certainly, he said, leftist figures in Spain from time to time criticize the Church to boost their own popularity and galvanize their base. But also, for the professor, culture is changing at a rapid and dizzying pace, and that change has the Church in its maelstrom.

If the square’s name is changed, then — regardless of whether it is a deliberately anti-Catholic move, or a sign of Spain’s growing apathy towards its Christian roots, or merely calculated political maneuvering — it is sure to create debate across the city and country.

And even if the proposed change doesn’t go ahead, the role of Christianity in Western countries remains in a state of flux.