Bishops, schism, and the SSPX

With the society announcing plans for an illicit consecration, what is the history and the law?

After the Society of St. Pius X announced this week that it plans to consecrate a bishop without a papal mandate in July, the prefect of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith has said Vatican talks with the society will continue, towards a goal of regularizing the group’s status in the Church.

While there is some speculation that the SSPX’s announcement is merely an aggressive negotiating tactic, questions have been asked about the likely canonical consequences should they proceed with such an action.

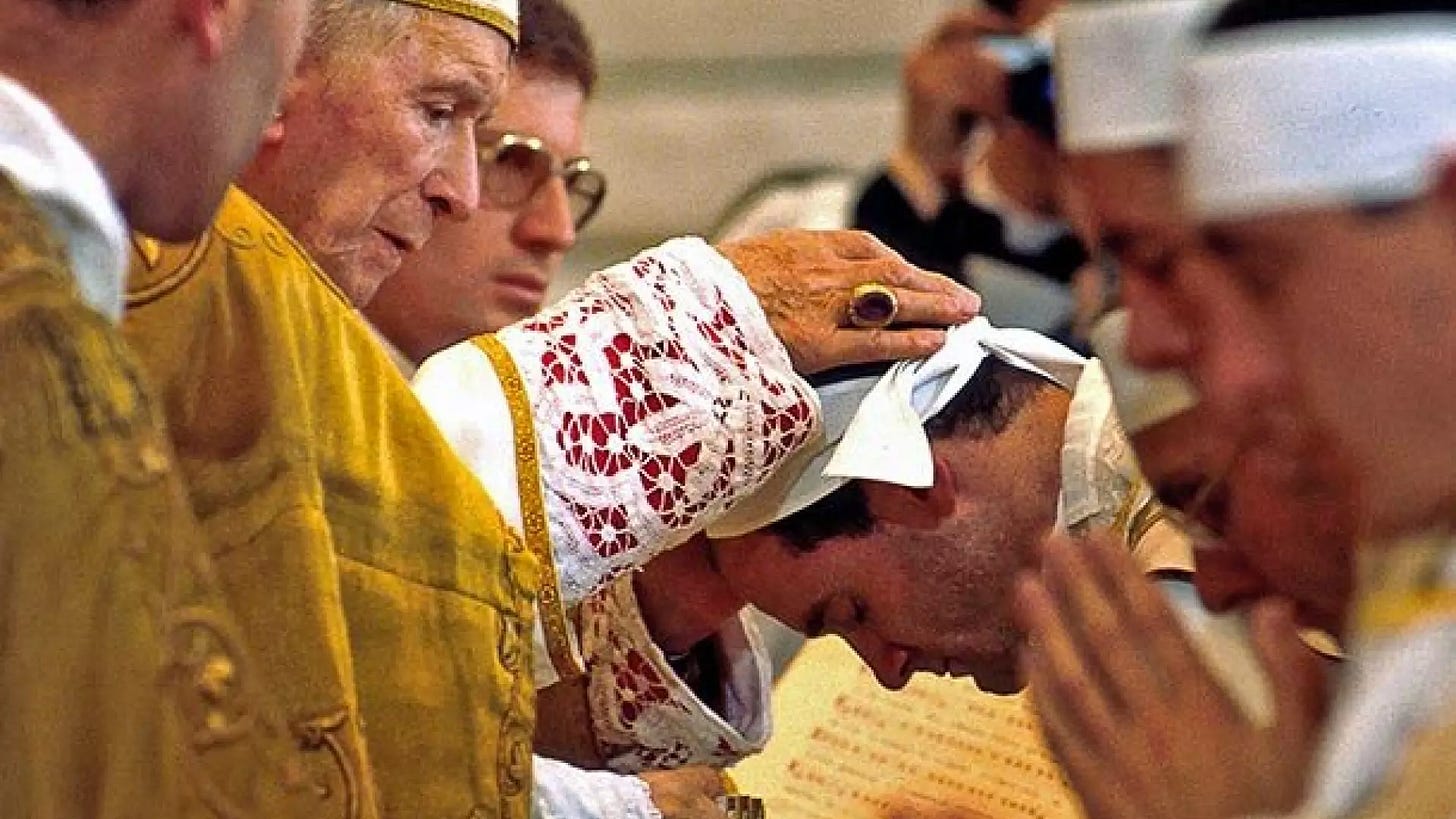

On the previous occasion on which bishops have been consecrated for and by the society, in 1988, the Holy See under Pope St. John Paul II declared that an excommunication latae sententiae had been incurred by the participants for an act of schism.

However, some online supporters of the society have sought to defend the society’s planned action. In doing so, they have attempted to draw parallels with previous instances where bishops have been consecrated, apparently without a mandate and without the same penalties being declared by the Holy See.

So, is the SSPX’s situation unique, and what does the law actually say?

The Pillar explains.

What does the Church’s law actually say about consecrating a bishop without a mandate?

Canon 1387 states that “Both the Bishop who, without a pontifical mandate, consecrates a person a Bishop, and the one who receives the consecration from him, incur a latae sententiae excommunication reserved to the Apostolic See.”

Canonically speaking, that is about as clear as a law can get:

A specific action is described — the consecration of a person. We can read “person” here to mean “man” for a few reasons, because only a man can be validly consecrated bishop and because the “attempted consecration” of a woman is treated in a separate canon.

Specific people are identified as subject to a penalty — both the bishop who performs the consecration and the man who receives it.

And a specific penalty is imposed: automatic excommunication, whose declaration and remittance is reserved to the Holy See. That penalty, it should be clear, follows the ordinary rules for such things established in canon law — in other words, the penalty has to be formally declared to take its full effect.

The wording of the canon is noteworthy because it criminalizes a specific action with an objectively binary condition — either there is or is not a papal mandate — and therefore seems to sidestep many of the usual other conditions which must be considered in the application of penal law.

For example, ordinarily it is necessary to establish “imputability” in penal cases, that the person is morally and legally culpable for the violation of the law, having sufficient freedom, a certain intention to do so, and awareness of the law.

In the case of illicit consecration, there is no plausible defence of ignorance of the law, and the participant’s motives for violating it are not at issue, beyond the possible defences of immediate and direct coercion — in which case things would get a little more complicated.

But everyone keeps talking about “schism” — is it schism to consecrate a bishop without a papal mandate?

Well, that depends on how precisely you want to phrase the question, really.

Schism is canonically defined as “the refusal of submission to the Supreme Pontiff or of communion with the members of the Church subject to him.”

Schism, in this sense, is a crime of discommunion, and fundamentally a crime of both intention and action, and the wording of the law sets up a series of measures for imputability, which would have to be met for the crime to be committed — to “refuse” one generally has to first be told something directly, so there would usually need to be either a clear and unambiguous warning to a person or group that a given act would constitute schism, or a refusal to retract afterwards.

Of course, some actions are so clear and deliberate that they are sometimes termed as canonical acts of schism without a warning, before or after the fact — if a cleric accepts a ministry position in a non-Catholic Church, for example.

Not every materially schismatic act is followed up by a formal ecclesiastical declaration of the penalty — which means that not everyone who commits an act of schism has seen the penalty of excommunication go into effect. But in the case of the SSPX bishops, the penalty was formally declared, and then remitted by Benedict XVI.

OK, but if illicit consecration is its own canonical crime, and ‘formal schism’ isn’t always that clear, why do people talk about ‘schism’ and the SSPX?

There are a few reasons.

First, the history: specifically, the last time the group acted to consecrate bishops without a mandate from the pope, back in 1988.

Prior to that event, the society, under Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, gave similar public notice of the consecrations ahead of time. In response, the Holy See warned explicitly that such an action was not permitted and that doing so would be a breach of communion — an act of schism.

In response to Lefebvre’s consecration of four men, Pope St. John Paul II wrote that “In itself, this act was one of disobedience to the Roman Pontiff in a very grave matter and of supreme importance for the unity of the Church, such as is the ordination of bishops whereby the apostolic succession is sacramentally perpetuated. Hence such disobedience - which implies in practice the rejection of the Roman primacy - constitutes a schismatic act.”

The society was warned not to carry on with the consecrations, and told specifically that doing so would be in willful and direct disobedience to the pope.

Lefebvre chose to do so anyway, the pope noted.

But he also pointed out that the society’s self-justification for doing so was itself a kind of imputable motive:

“The root of this schismatic act can be discerned in an incomplete and contradictory notion of Tradition,” wrote John Paul. “Especially contradictory is a notion of Tradition which opposes the universal Magisterium of the Church possessed by the Bishop of Rome and the Body of Bishops. It is impossible to remain faithful to the Tradition while breaking the ecclesial bond with him to whom, in the person of the Apostle Peter, Christ himself entrusted the ministry of unity in his Church.”

As such, John Paul declared the penalty of excommunication against all five men, defining them as schismatics by doing so.

It is interesting to note that the pope clearly thought that the schismatic nature of the act in the circumstances needed to be both fully described and punished canonically.

John Paul II could have invoked the relevant canon on illicit consecration, declared the same penalty, and avoided imputing the participants with a schismatic motive, but the pope instead judged the circumstances and motive to be sufficiently schismatic as to be unignorable, and requiring a response.

And it is worth noting that the current superior of the society has made it clear this week that he believes “the fundamental reasons that justified the consecrations of 1988 still exist and, in many respects, impel us with renewed urgency.”

So, to be clear, the society is still relying on the same justification as in 1988 for any new consecrations — and those justifications have already been assessed by St. John Paul II.

—

Since then, the language of schism hasn’t been formally revoked, even when the Church has used other rhetoric to describe the group — the Holy See has often preferred to speak of the society as being in “irregular” or “imperfect” communion. At least some experts view that as an exercise in politely veiled language; figuring that one is either in communion, or one is in schism, whether material or formal.

For some, the matter has seemed a bit muddled since Pope Benedict XVI lifted declared excommunications on the surviving SSPX bishops in 2009, leading some to claim a new status, or era, for the entire society.

But when he did so, the pope aimed to clarify that his move was personal, not institutional, and changed nothing for the society as a group.

Benedict explained that “The excommunication [and its lifting] affects individuals, not institutions. An episcopal ordination lacking a pontifical mandate raises the danger of a schism, since it jeopardizes the unity of the College of Bishops with the Pope.”

“The remission of the excommunication was a measure taken in the field of ecclesiastical discipline: the individuals were freed from the burden of conscience constituted by the most serious of ecclesiastical penalties,” Benedict wrote.

“In order to make this clear once again: until the doctrinal questions are clarified, the Society has no canonical status in the Church, and its ministers – even though they have been freed of the ecclesiastical penalty – do not legitimately exercise any ministry in the Church.”

In other words, Pope Benedict was clear that he intended his act — lifting excommunications — to be a personal act, for those particular bishops, and not a kind of institutional approval.

The pope did not explicitly state that the SSPX is a formally schismatic institution, though he appeared to describe it as such.

But doesn’t that make canon 1378 redundant?

If illicit consecration is an act of schism, and schism has the same penalty, why have two separate canonical crimes?

That’s a smart question.

Schism is a crime of disposition and intention as much as action, and not every illicit consecration without a papal mandate is necessarily schismatic.

Consider a hypothetical case in which a bishop doesn’t have a papal mandate but, for some reason, he thinks there is an overwhelming urgency to him consecrating someone as a bishop anyway.

Hypothetically, that would still be a criminal act, and it would still incur the penalty of excommunication for all involved. But if it wasn’t preceded by a back-and-forth with the pontiff, or with explicit orders from the Holy See not to proceed, it could be argued to fall short of the “refusal to submit” description of schism in the law.

And it’s worth noting that the canon on illicit episcopal consecration has gone through reforms in recent decades. Before the promulgation of the 1983 Code of Canon Law, the relevant canon took a different approach to the issue:

Canon 2370 of the 1917 Code of Canon Law stated that “A bishop consecrating another bishop, with the assistant bishops or, in the place of bishops, priests, and those who receive consecration without an apostolic mandate against the prescripts of [the law] are by the law suspended until the Apostolic See dispenses them.”

Note two significant things about that canon:

First, the previous code provided only a suspension, not an excommunication — barring bishops involved from exercising their office.

That is a markedly different provision, one which appears more aimed at recognizing the irregularity of what has been done and the need to rectify it, rather than assigning the maximum medicinal penalty. And the change to a stricter penalty is remarkable, given that the 1983 code set out to eliminate automatic excommunications whenever possible.

Second, the phrasing of canon 2370, “until the Apostolic See dispenses them,” sets up a presumption in law that those involved will be — and intend to be — regularized with and recognized by the Holy See, and do not intend to minister in a state of schism.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean the illicit consecration was not a crime before to the 1983 code — but the prior law seemed to foresee circumstances in which such consecrations might happen without the kind of schismatic intent identified in 1988 by Pope St. John Paul II, with regard to the SSPX.

What about Cardinal Slipyj? Didn’t he consecrate bishops without permission?

In discussion of the SSPX situation, an historical example is often raised — the situation of Cardinal Josyf Slipyj, who in 1977 consecrated bishops without a papal mandate.

But it’s not entirely a parallel situation.

Slipyj was head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church during the first decades of the Cold War; he spent years in prison and labor camps under the Soviet regime, before he was released in the 1960s.

The Vatican, via its practice of Ostpolitik, had a policy against consecrating bishops for countries behind the Iron Curtain.

But in his 80s, while living in Rome, Slipyj conferred consecration on several Ukrainian Greek Catholic priests without a papal mandate, apparently because he was afraid for the demographic future of the Ukrainian Church.

St. John Paul II would later install one of those bishops as head of the UGCC, and make him a cardinal.

Some supporters of the SSPX have pointed to the cardinal’s example, noting he faced no known canonical sanctions for his actions.

But it’s worth noting that Slipyj was an Eastern Catholic — the provisions and penalties of the 1917 and 1983 codes, which are for the Latin Catholic Church, did not apply to him.

His actions also predated the universal code for the Eastern Churches, which contains a similar canon to the 1983 code, but which was not promulgated until 1990.

Slipyj’s actions were certainly illicit. But direct canonical comparison between him and the Lefebvre situation is not exactly possible — nor exactly appropriate.

And after his consecrations, the law changed, so that by the time of the 1983 code’s promulgation, the Holy See judged that consecrations without mandates warranted a harsher penalty.

But what about China? There’s a lot going on with illicit consecrations there, right?

Another perceptive question. There’s a lot you can say about China.

For a start, until the Vatican’s 2018 provisional agreement with Beijing on the appointment of bishops, there was a parallel, state-sponsored, schismatic church in operation in mainland China, which routinely consecrated — illicitly — bishops for its own dioceses and, in some case, claiming them as rival leaders of Rome-recognized dioceses.

Those bishops were subject to the ordinary automatic excommunication for illicit consecration without a papal mandate. And, because the state-sponsored Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association explicitly rejected the Apostolic See’s authority over the Church in China, it was a formally schismatic group.

But following the 2018 deal, those excommunications were lifted by Rome — bringing the state church into communion with Rome was half of the deal’s whole point.

Gaining some legal recognition for the underground Church in China was the other half, and the deal hasn’t been a great success at that, to be sure.

But, sticking to the specific question of illicit consecrations, it’s also true that Beijing has proceeded with a slate of episcopal consecrations that seem to be done without papal mandates. In fact, most informed observers would say they are absolutely being done without papal mandates.

Rome’s response to those events has been largely to claim after the fact that everything is fine, that the pope knew and approved in advance, however incredible that may sound, and however much reporting suggests the opposite.

But Rome has also tended to say that those episcopal consecrations are being conducted “in line with the provisions of the agreement.” Since the terms of the deal are secret, that claim is unfalsifiable. (Unless any reader has a copy of the China deal, and can pass it on to The Pillar.)

Quite how much that agreement dispenses from canon law, or augments it, is simply a known unknown.

In short, whatever agreement the Vatican has made with China, it can and does exist outside of the otherwise universal dictates of canon law.

—

There is a related question about the CPCA and its stated assertion that religious groups in China must be autonomous from any foreign power — which on paper reads like a fairly clear schismatic claim.

But given the Holy See’s explicit advice to Chinese bishops, that they can make — and even ought to consider making — a “reservation of conscience” against anything the CPCA claims against Church doctrine or ecclesiology, and given the private assertions of some bishops, that they do recognize the pope’s authority, it’s clear there are at least open questions of imputability and coercion at play.

None of this is the case with the SSPX’s stated intention.

So if the SSPX do go ahead with the consecration in July, is it schism?

A lot of people will think so, that’s for sure. But exactly what will happen depends on what happens between now and then, and ultimately what Pope Leo XIV decides to do.

If the Vatican issues the same kind of explicit warnings which preceded the 1988 consecrations, and the society carries on in spite of them, it would be hard to argue for a different judgment from the pope in response.

That said, Leo could, if he wanted, narrowly apply the law of canon 1387 and declare the excommunications on those grounds alone, without invoking the law on schism.

That decision would likely trigger a round of debate about whether the participants are, formally speaking, “in schism” — though they would still all be excommunicated.

It would be for Leo, himself a canonist, to decide if there was a particular point he wished to make through applying the law in that way.

I enjoyed the Pillar congratulating itself at how perceptive its own questions were.

Thanks for these explainers - they are incredibly helpful.