Inside the ‘compromise’ over Spain’s Civil War memorial

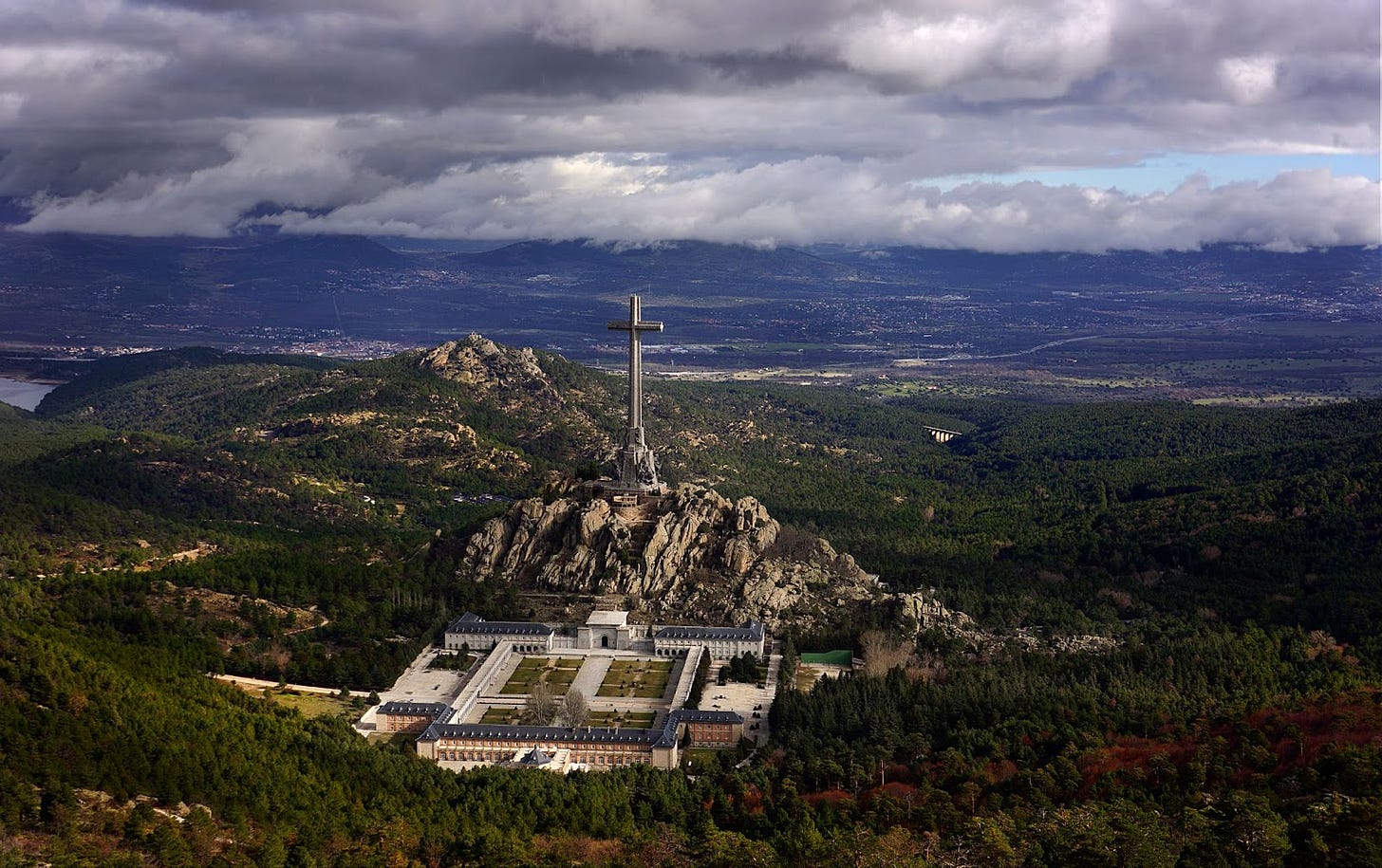

The Valley of the Fallen was meant to be a symbol of reconciliation, instead it has become a perennial flashpoint

Almost 85 years after General Francisco Franco led the Nationalists to victory, the Spanish Civil War is the kind of conflict that just refuses to die — and continues to motivate social discussion and strife across Spain.

Few symbols express this more deeply than the Valle de los Caídos,…