‘Into the One Fold of the Redeemer’: Robin Ward’s path to Rome

“I do feel a palpable sense of communion”

A rare ray of sunshine broke through the murk of social media last weekend when the Anglican Canon Robin Ward posted an update announcing that he had been received into the Catholic Church.

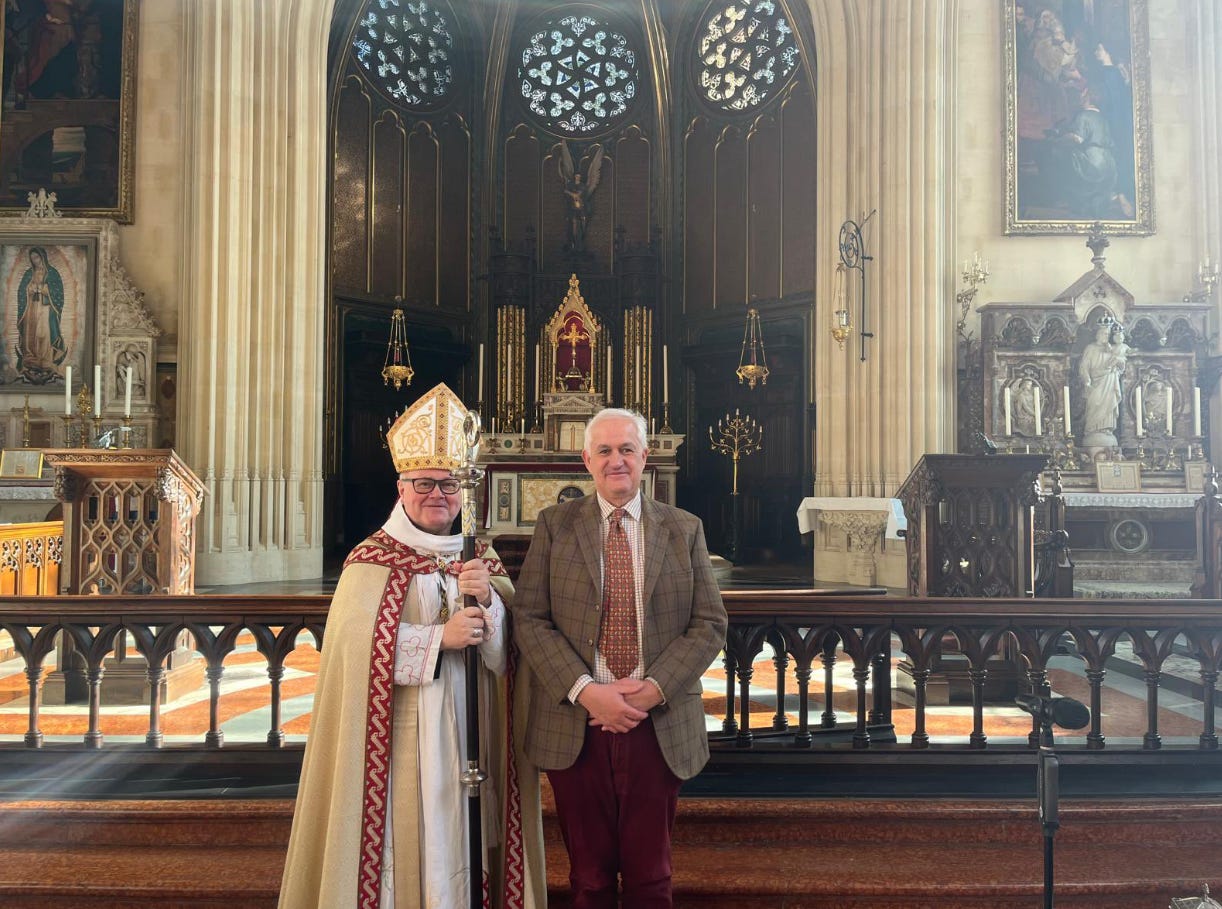

The post, accompanied by a photograph of himself standing next to a Benedictine abbot, has been viewed almost a quarter of a million times.

For decades, Ward has been a well-known figure in England’s Christian circles. He has embodied the Anglo-Catholic tradition, an Anglican subculture that stresses the Church of England’s debt to pre-Reformation forms of Christian life.

For almost two decades, Ward led the Anglo-Catholic bastion of St. Stephen’s House, Oxford, an Anglican theological college nicknamed “Staggers.” But he did not, in fact, grow up in high church Anglican circles. He was raised in a more consciously Protestant low church tradition that nevertheless had a sacramental element.

Ward had an elite education, studying at the City of London School, whose past students are known as “Old Citizens”, and Magdalen College, Oxford, where he became immersed in Anglo-Catholicism. He trained for the Anglican priesthood at St. Stephen’s House, developing an expertise in patristics, the study of the Church Fathers. His doctoral thesis was on “The Schism at Antioch in the Fourth Century.”

Inevitably, Ward was drawn into the Anglican Communion’s bruising theological and ecclesiological debates, standing up for what he perceived to be the imperiled Catholic tradition within the Church of England.

He returned to St. Stephen’s House in 2006 to serve as principal, helping to oversee the formation of generations of Anglican clergy. He taught those preparing for ordination that they should keep three questions before them: Who is Jesus Christ? What is a priest? What is the Church?

The final question nagged at him. His search for an answer led him to step down as principal in April 2025 and to seek reception into the Catholic Church at the age of 60.

Ward, a married man with two sons, now lives in Cornwall, a county on the southwestern tip of England, known for its wild and rugged coastline. He spoke with The Pillar about his path to Rome, his sense of being accompanied on his journey by St. John Henry Newman, and his future plans.

How would you describe your spiritual journey up to this point?

I was brought up in the habits of a low church Anglicanism that barely exists any more: using the Book of Common Prayer, liturgical without ceremony, earnest and lengthy in its preaching, sacramental but Protestant.

It was not until I arrived at Oxford to read medieval English at Magdalen College (C. S. Lewis’ subject and home, although he was not remembered fondly there after “That Hideous Strength”), that I discovered the rarified and recondite world of Anglo-Catholicism.

To those outside it, especially perhaps to Catholics, this surviving fusion of 19th-century theology and romantic ritualism cannot but appear eccentric and marginal, but in the mid-1980s it still had the power to captivate and inspire me.

I trained for the priesthood at St. Stephen’s House, the most “extreme” of the Church of England’s colleges, and went on to serve for 15 years as a parish priest, until returning to Oxford and the college for 19 years as principal.

During my time there, I taught several generations of ordinands patristic, moral, sacramental, and liturgical theology, and also contended for what I understood to be catholic faith and order in the Church of England, as a variety of developments seemed to occlude what I held most dear.

Were there any major turning points on your path to reception in the Catholic Church?

To run a seminary is, at its most simple, to propose three questions to those who come: Who is Jesus Christ? What is a priest? What is the Church? As time passed I found that the answer I was able to give to the last question was less and less satisfactory, and that this was becoming more apparent not only to me but to my students, past and present.

I was also brought into close proximity with the energy and charity of Catholic life in Oxford: The Dominicans at Blackfriars, the Jesuits at Campion Hall, the Oratorians at St. Aloysius’.

And of course behind all this was the constant presence of John Henry Newman: in the 1980s, Newman was “at the end of the beginning” of his rediscovery, someone to whom justice hadn’t been paid; 40 years on, Newman as saint and Doctor is the teacher of our age, as Augustine was for Antiquity and Aquinas for the Middle Ages.

As we have learned to understand him better, so I have learned to see through his distinctive charism, so close to the Oxford I have known and loved for so long, the way into the One Fold of the Redeemer. I took John Henry as my confirmation name.

Were there any other Catholic individuals who personally inspired you?

I have been very grateful for the patient accompaniment of many Catholic friends, some of whom I know have prayed for me for many years. And I have been fortunate to witness at first hand the very vigorous and varied Catholic life that I experienced in Oxford during my time there.

And I think for all Catholic-minded Anglicans who have converted, the example and writings of Pope Benedict XVI have been seminal guides into the Church.

You have long been considered a leading figure in the Anglo-Catholic movement within the Church of England.

Were you worried that your entry into the Catholic Church might be demoralizing for the movement?

The Parting of Friends, as Newman put it, has almost been what one might call an occupational hazard of being an Anglo-Catholic since 1845.

Dedicated and committed people whom I admire and respect will remain in the Church of England, but the Oxford Movement was fundamentally about the doctrine of the Church, a question of ecclesiology, and so the questions and difficulties that led me to make this move will remain for them to resolve in their own way and their own time.

How did you come to be received by Abbot Cuthbert Brogan, O.S.B., at Farnborough Abbey?

I had never been to Farnborough Abbey. But the abbot regularly took part in events at the Catholic Halls in Oxford, and I got to know him a bit there. I knew that he would understand my situation and be able to make a prudent judgment about whether I was ready. I am very grateful to him and to the community at Farnborough for the gracious and hospitable welcome I received.

Is there anything about becoming a Catholic that has surprised you?

Not so far, less than a week in. I am very fortunate to have a Catholic parish church with a thriving life less than five minutes from my front door, and I look forward to taking part there.

But I do feel a palpable sense of communion — substantive ecclesial communion — with the chief pastor of the Church and with him over a billion fellow Catholic Christians.

Are there any thoughts you’d like to share about your future involvement in the life of the Catholic Church — perhaps in relation to joining the personal ordinariate or priestly ministry?

For the future, I now need to learn how to live within the household, and to trust in God’s providence for the work and vocation He intends for me: “One step enough for me.”

I have been tremendously encouraged by the kindness of so many, not least those who for many years have been praying for me, and I rejoice without regret or hesitation to find myself in this place.

The popes have asked that Anglican converts should preserve their patrimony through the ordinariate where that is possible, but there is no ordinariate community near where I live in Cornwall at the moment. So we shall see how that might work out in the future.

I’m very grateful for the messages of goodwill and support that I have received. Some people have asked why I have taken so long, to which I reply – Sero, sed serio!