Is Teilhard de Chardin being rehabilitated? And who is that, anyway?

Is Pope Francis bringing a controversial theologian back into vogue?

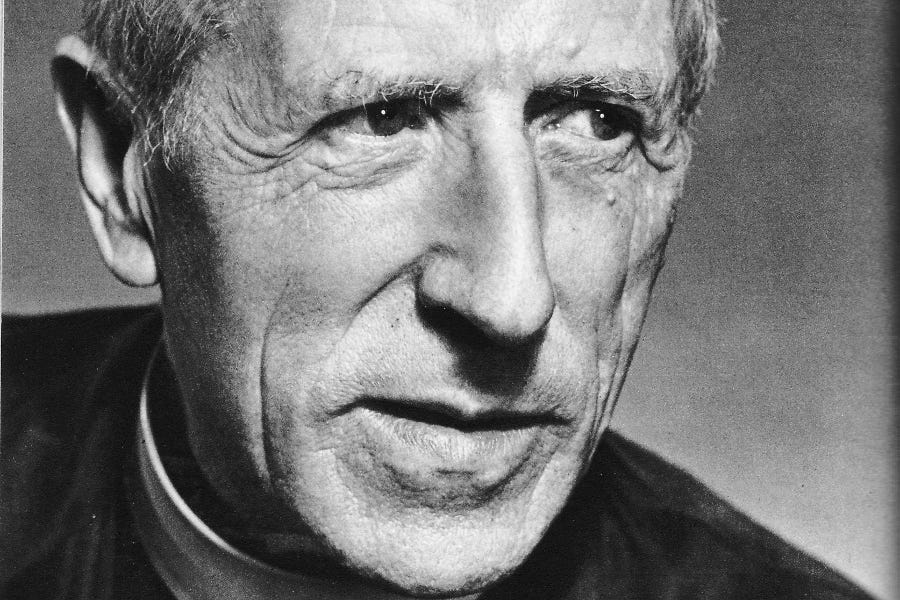

The French Jesuit priest Pierre Teilhard de Chardin has been called many things since his death in New York in 1955.

To some, he is a creative thinker “in the same league as Einstein.” To others, he is “the most influential heretic of the 20t…