Life in 'El Chipote' - A Nicaraguan priest's story of prison, torture and exile

After arrest with Bishop Rolando Alvarez, an exiled Nicaraguan priest tells his story

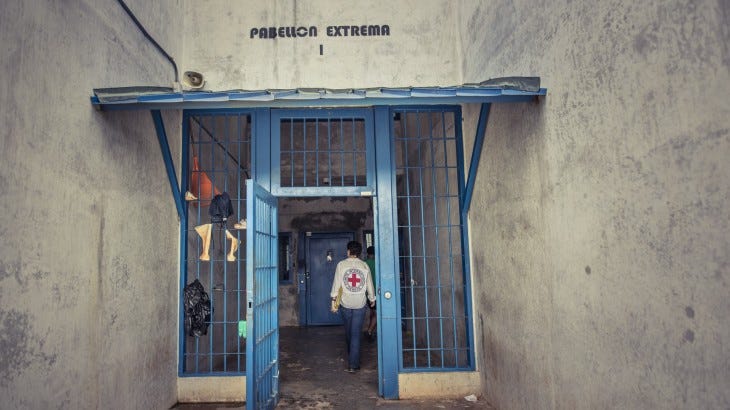

Last August, a small group of priests, seminarians, a deacon, and a few lay people were held by police in an unofficial house arrest in the home of Bishop Rolando Álvarez of Matagalpa, Nicaragua, who was imprisoned with them.

The detention came after Álvarez protested a government decision to close 10 radio stations in his diocese.