The Altars of St. Mary’s – Part 1

A history of freestanding altars & Mass facing the people at Notre-Dame de Paris

It has been just more than one year since the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris officially reopened, following five years of intensive reconstruction after the calamitous fire which had threatened to destroy the building in April 2019.

Most of Notre Dame’s restoration efforts have met widespread acclaim, because of their exceptional quality, attention to detail, and careful replication of original 13th century craftsmanship techniques and materials.

But not all aspects of the cathedral’s rehabilitation are without controversy. For example, French president Emmanuel Macron has faced widespread public opposition over his plan to replace six stained glass windows from the 1800s with new contemporary designs, even though the windows were not damaged in the fire.

Due to state secularism laws in France, the state owns and operates the Cathedral of Notre Dame, and the French state has been responsible for the design and restoration of the building.

The Archdiocese of Paris, meanwhile, is responsible for the interior furnishings and liturgical elements of the cathedral – such as the chairs, baptismal font, altar, reliquaries and shrines.

The archdiocese’s choice of design for new liturgical furnishings has also proven controversial.

After a call for artists to submit design proposals for a new altar and ambo, a submission by designer Guillaume Bardet was selected. It has met with a variety of reactions – both positive and critical – since its June 2023 unveiling.

The new altar in particular was the focus of criticism, especially from commentators who thought the striking modern design, and its freestanding orientation and placement in the transept, were a radical departure from the traditional Gothic character of the high altar and the rest of the building.

The architecture of a cathedral

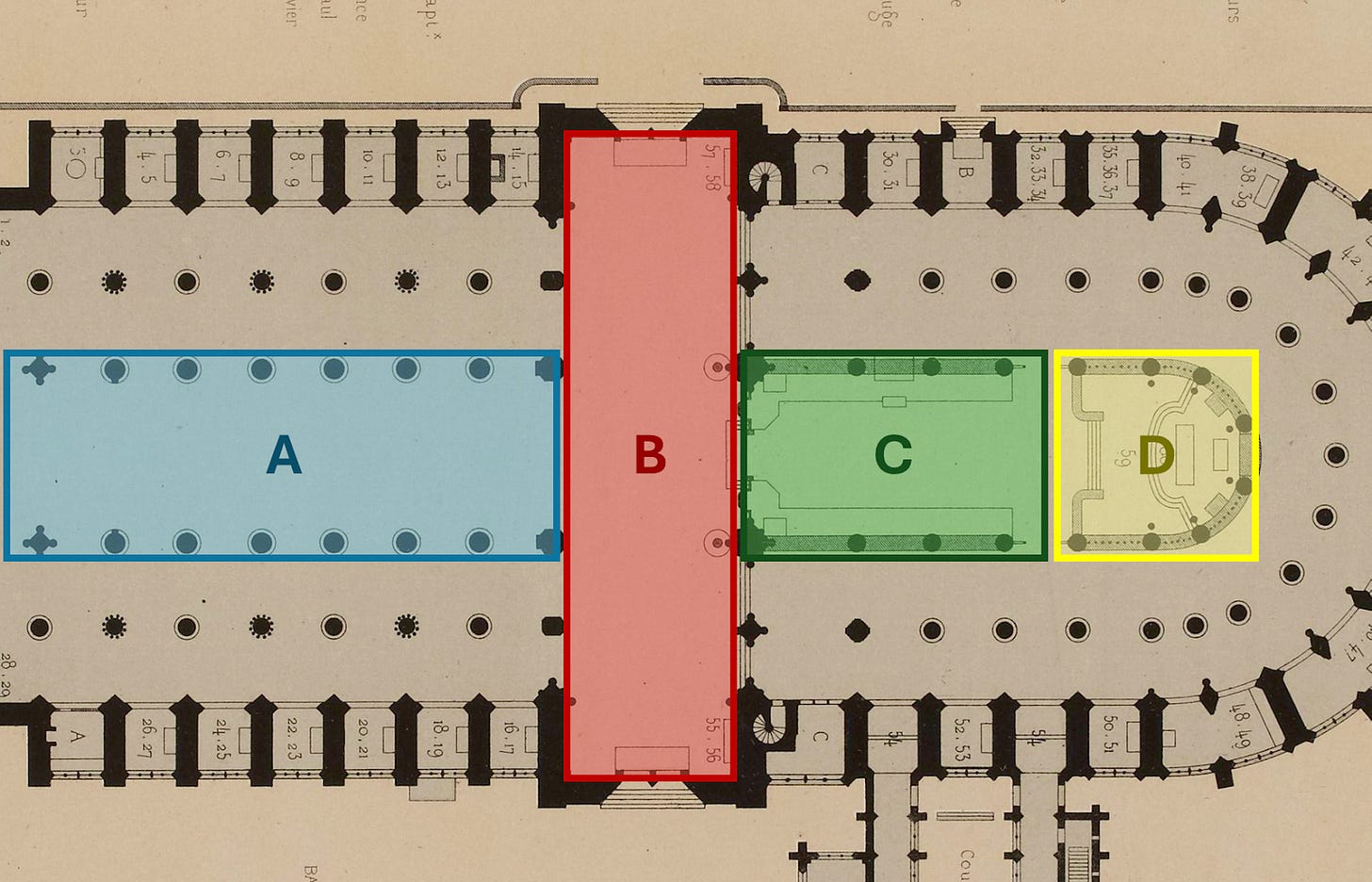

The area labeled “A” is the nave, where the congregation sits; “B” is the transept; “C” is the choir, also known as the ‘chancel’ which sometimes was separated from the transept by a decorative grille or barrier called a ‘rood screen’; and “D” is the apse, a semicircular area which contains the sanctuary and the high altar.

But the recent restoration was not the first time that the altar of Notre Dame had been subject to criticism. In fact, before the 2019 fire, Notre Dame used a modern freestanding altar on a pedestal in the transept.

That altar – which received mixed reactions in French society and was sharply criticized by traditionally-oriented Catholics – was created by sculptor Jean Touret at the request of Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger, Archbishop of Paris, in 1989.

It was a metal cube decorated with abstract representations of the four Evangelists and four Old Testament prophets.

The 1989 modern freestanding altar – located in the transept, outside of the traditional sanctuary, in order to be closer to the people – offers a sharp contrast with the older high altar, which remains at the far end of the apse, separated from the congregation by the choir and a fair distance.

Priests at the high altar would offer the liturgy in a manner now referred to as ad orientem (“toward the East”), facing the same direction as the congregation, while the modern altars were designed so that Mass is celebrated versus populum, facing toward the people.

It is widely assumed that the Second Vatican Council was the impetus for the move at Notre Dame to add freestanding altars in the transept and Mass versus populum.

After all, it was during and after the council that the vast majority of Roman Catholic church buildings around the world were modified in a similar manner to accommodate the celebration of what was termed “the New Liturgy.”

But the history at Notre Dame is not the case.

There is, in fact, a long history of freestanding altars being erected in the transept in Notre Dame Cathedral – for more than a century before the Second Vatican Council. Likewise, Masses facing the people were regularly celebrated in Notre Dame beginning in the 1930s.

These versus populum Masses were not performed in secret by radical innovators. They were celebrated openly by subsequent archbishops of Paris and other major prelates, like Vatican Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli (the future Pope Pius XII), and had even been shown on TV broadcasts throughout Europe as early as 1954.

The council and the post-conciliar renovations

The story of the 16th century Council of Trent may sound familiar, following a pattern similar to that of another council held four centuries later.

After the ecumenical council, the pope established a commission to undertake a reform and standardization of the liturgical books in light of the council’s directives.

In addition to the revision of the liturgical books, it soon became clear that there was interest amongst various prelates and clerics for physical renovation and changes to altars and church buildings.

Even though those things had not been explicitly mentioned in the conciliar decrees, it appears to have been widely believed that church buildings and sanctuaries should be modified to reflect both the intentions of the council fathers and the era’s prevailing liturgical opinions: Interiors should be simplified and decluttered, some side altars and rails should be removed, and the high altar should be modified and moved closer to the people to improve their ability to see what was happening.

These changes were welcomed and embraced in some places, but met with stiff resistance in others.

Even before the Council of Trent, there was already interest among Catholic architects and some of the clergy to modify the layout of church buildings, altars, and sanctuaries to improve the visibility, understanding, and access of the laity.

A number of churches throughout Italy and elsewhere were built or renovated in the early- to mid-1500s to offer an unobstructed view of the high altar, to move the high altar closer to the nave, and/or to move the choir behind the high altar so that it would not act as a barrier between altar and people.

Indeed, according to art historian Marcia Hall, “an aesthetic preference had already developed by the 1470s for unified churches without interrupting rood screens.”

Elsewhere, Hall summarizes that “[t]he more we learn about the Counter-Reformation the more Trent turns out to have been not so much the initiator of reform as the codifier of it … In church renovation, as in many other areas, the codification succeeded a widely recognized need for reform.”

Even though ideas for a new approach to church interiors and altars predated the Council of Trent, focus on the issue intensified after the council and throughout the Counter Reformation period.

The Council of Trent issued no specific decrees about church architecture. Nevertheless, it was widely understood that the bishops at Trent had clear opinions and desires regarding a change in direction for the arrangement of altars and churches.

The Tridentine approach would be one which emphasized visibility, accessibility, and simplicity.

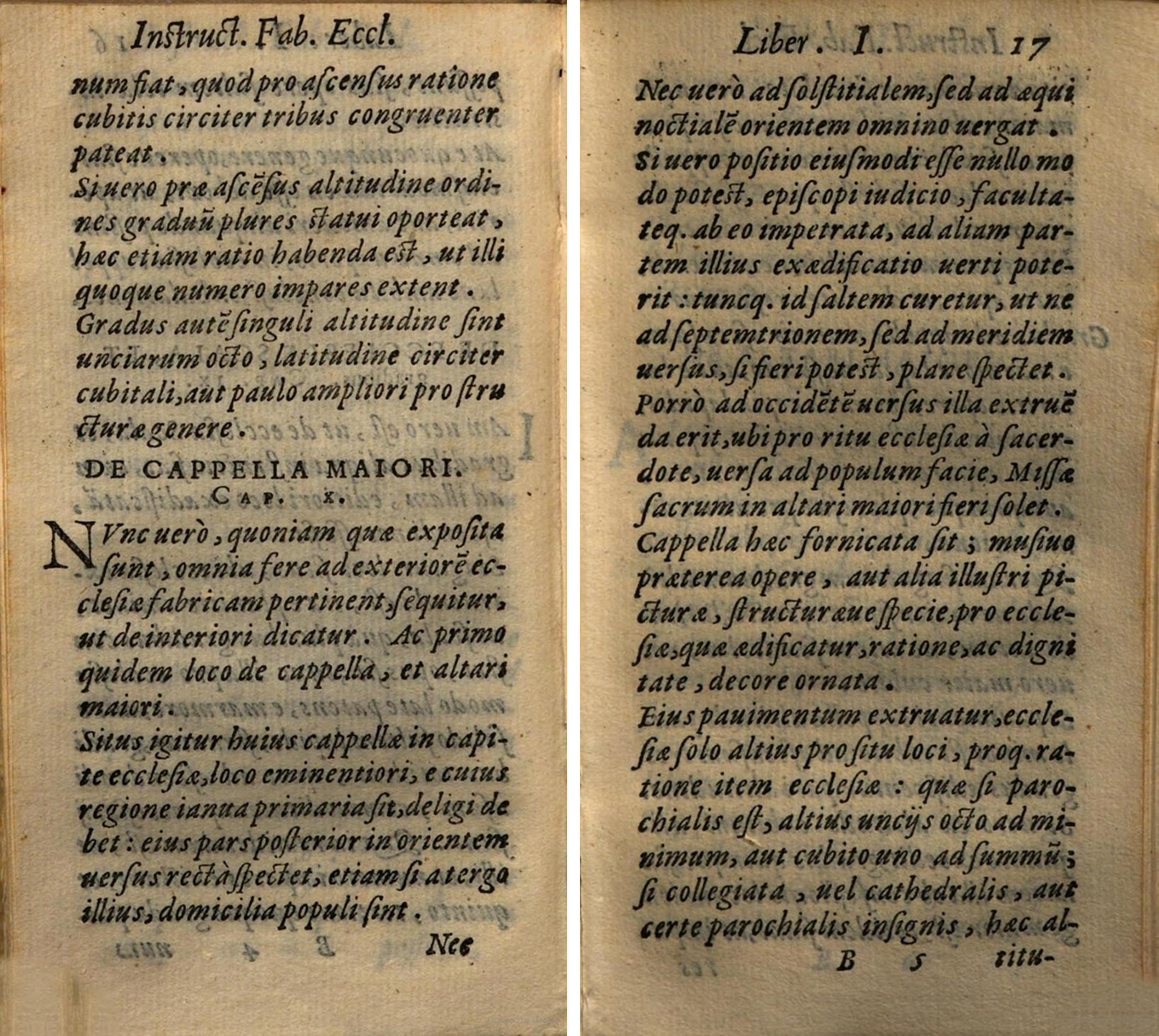

In 1577, Charles Borromeo issued a set of instructions which legislated the design and furnishing of churches in Milan – the “Instructiones Fabricae et Supellectilis Ecclesiasticae.”

This document was understood to reflect the prevailing attitudes of the hierarchy regarding church architecture – in the introduction, Borromeo even explicitly tied the instructions to the desires of the council fathers – and was deeply influential both in his Archdiocese of Milan and throughout the wider Church for centuries afterward.

Among other things, Borromeo instructed that a church’s main altar be freestanding and elevated (emphasizing visibility for the laity) and even offered the possibility for the priest to celebrate Mass “with his face turned toward the people” after the manner unique to the ancient Roman basilicas.

Liturgical scholar Fr. Uwe Michael Lang describes these instructions as a significant contribution to the development of liturgical spaces, offering “a clear view of the sanctuary with a focus on the high altar and the tabernacle … aiming above all at the visibility of the liturgical action, which was meant to facilitate the participation of the faithful.”

In the decades which followed the council, subsequent popes worked to enforce adoption of the conciliar directives and to ensure that general papal vision for the Counter Reformation was being implemented.

Some popes even arranged apostolic visitations of certain cities, dioceses, or regions to assess the situation and make recommendations. These were focused on overseeing adoption of specific conciliar decrees, but also the broader focus on church architecture.

In 1581, for example, Pope Gregory XIII ordered an apostolic visitation of all the churches in the Republic of Venice. The purpose of this visitation – which had been arranged at the insistence of Charles Borromeo – was to survey the physical arrangements of church interiors (specifically rood screens, choir areas, and altars) and to make recommendations for renovations.

The visitation included the inspection and documentation of more than 100 churches – at least 71 parish churches and at least 34 monasteries and convents – and resulted in recommendations or orders for interior renovations for nearly all of them.

The recommendations of 1581 apostolic visitation served as the catalyst for an extensive construction and renovation program which touched most of the churches of Venice.

Within a decade or so, almost every single rood screen in the city was removed (with a few notable exceptions), many high altars were moved closer to the nave, and choirs were moved behind the altar.

This was not a phenomenon limited to Venice. In Italy and throughout Europe, there was a growing focus on promoting and standardizing liturgical rites, practices, and church architecture in a “Roman” fashion. With respect to church sanctuaries, the adoption of “Roman” style meant an emulation of the particular and unique arrangements of the old basilicas of the city of Rome.

This “Romanizing” process resulted in renovations throughout Italy. According to art historian Marcia Hall, “[m]ost of the tramezzi [Italian rood screens] in existing churches were torn down and the choirs transferred behind the high altar after Trent.”

Some of these renovations were made as a result of episcopal mandates. In other instances, renovations of this kind were freely and eagerly adopted because they reflected most fashionable architectural trends.

In some cases, even Vatican curial departments were responsible for directing and encouraging the “Romanizing” liturgical rearrangement of church sanctuaries during this period.

For example, on October 9, 1610, the Sacred Congregation of Rites issued a decision regarding the arrangement of the altar and sanctuary in the Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Troia, Italy:

“Cardinal [Domenico] Pinelli further declared that it would be more decorous, more fitting, and more convenient both for the bishop, the dignitaries, and the canons, and also for all the people who come to the church to hear the divine offices, if the altar were brought forward and placed in the middle near the entrance of the choir, so that the priest celebrating at it might turn his face toward the people.”

These examples help to illustrate the wide-ranging program of architectural transformation which accelerated after the Council of Trent, leading to church layouts with more visible high altars and shallower sanctuaries.

Tridentine reform and French cathedrals

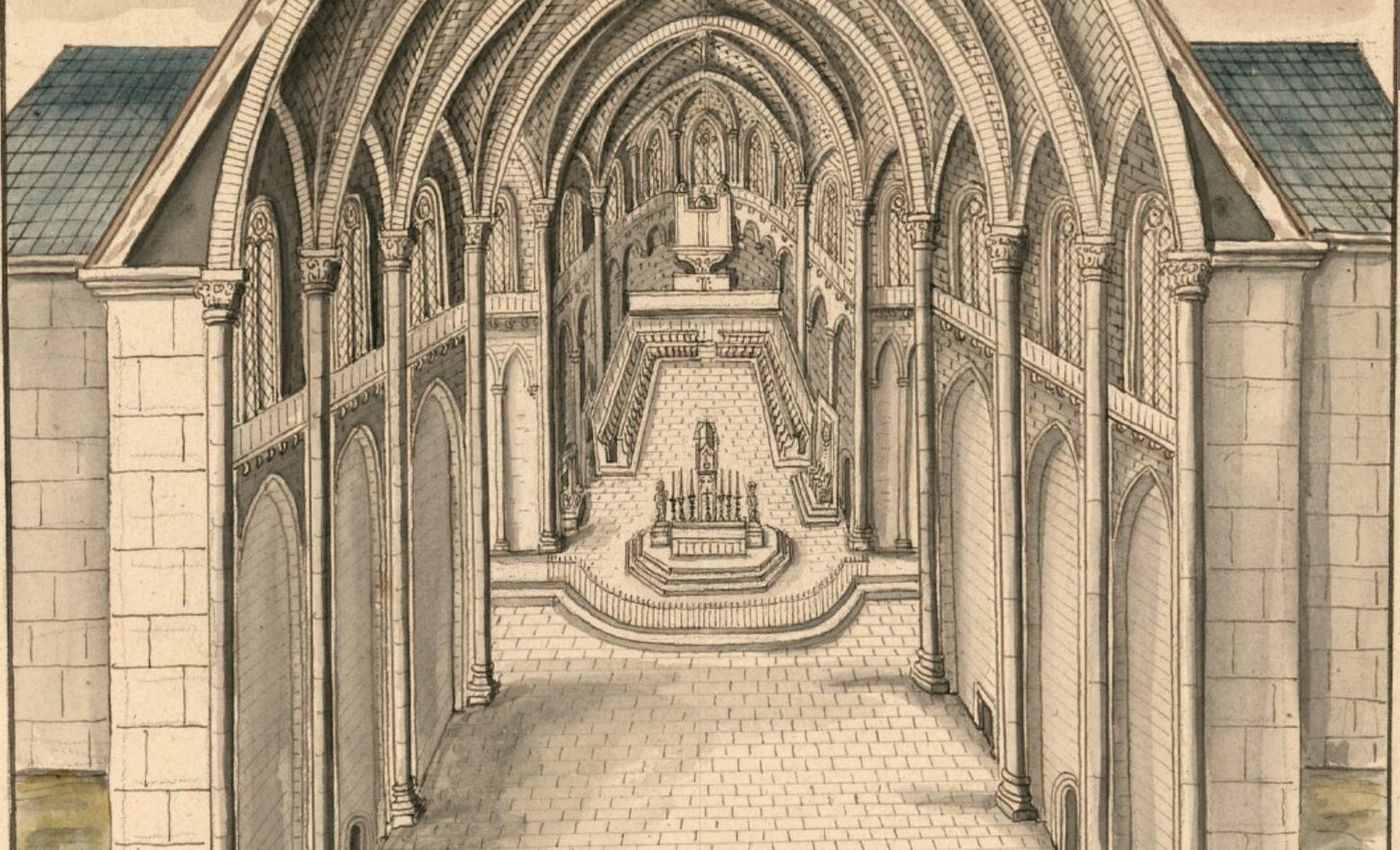

At the turn of the 17th century, a few decades after the Council of Trent, the choir, sanctuary, and high altar of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris looked much the same as it had three or four hundred years prior in the High Middle Ages.

In 1638, French King Louis XIII placed himself, his kingdom, and all French people under the protection of the Blessed Virgin Mary through an extraordinary act of consecration which was promulgated as a binding law known as The Vow of Louis XIII.

This act of Marian consecration was accompanied by pledges and promises of acts of devotion and thanksgiving which the king and the French people would render to Our Lady.

One of Louis’ most significant promises was to build a new high altar at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, one which would feature a sculpted representation of him surrendering his crown to the Blessed Virgin Mary, who would be depicted holding Christ in a version of the Pietà. This vow was left unfulfilled at the time of Louis’s death in 1643.

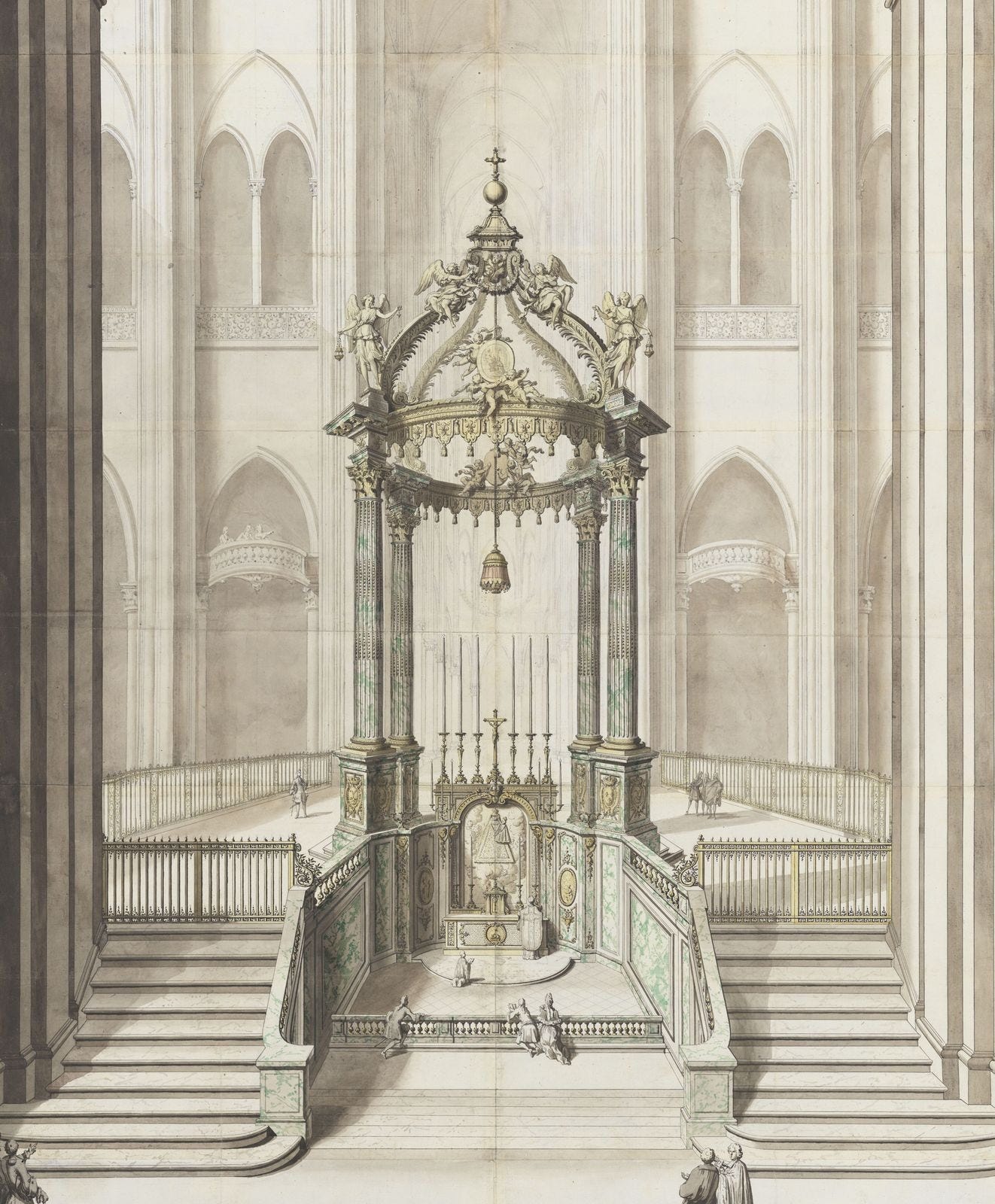

More than 50 years later, his son, King Louis XIV, sought to fulfill his father’s vow with respect to a new high altar at Notre Dame. In 1698, he charged Archbishop of Paris Louis-Antoine de Noailles to work with Jules Hardouin-Mansart, the king’s personal architect, to design the long-awaited new high altar.

The core vision for the project was that the new high altar would be modern, fashionable, and ‘Tridentine’: it would be freestanding under a baldachin with columns, in the style of Bernini’s famous altar in St. Peter’s Basilica.

In April 1699 work commenced on the renovation of Notre Dame. The rood screen was partially demolished, along with the old choir and medieval high altar, and the ceremonial first stone for the new altar was laid and blessed on Dec. 7 of that year.

Notre Dame was not the only major French cathedral to embark on a renovation of that kind. That very same year, in 1699, the Cathedral of St. Maurice in Angers completed a dramatic interior renovation: the old medieval high altar was removed, the choir was placed at the rear of the apse, and a new freestanding high altar was moved to the transept.

The first plan by Mansart envisioned Notre Dame’s new high altar and baldachin to be erected where the original high altar had been, still separated from the nave by the choir and a partial rood screen. But when the king visited Notre Dame in person to inspect the project on May 20, 1701, he disliked the altar’s proposed location.

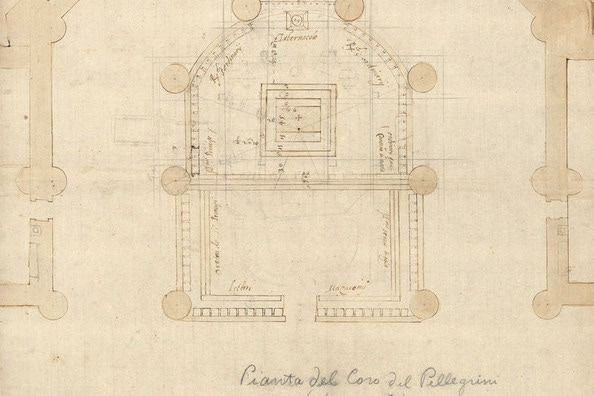

Because of this, at least two additional ideas for the altar were developed. A second proposal involved removing the rood screen completely and moving the altar closer to the nave, at the entrance to the choir (an illustration of this concept can be seen here).

A third proposal – the boldest of all – would have moved the altar into the transept itself, almost to the nave.

Neither of those new proposals were immediately acted upon, due to a variety of difficulties which beset the kingdom at this time. Ultimately, two critical developments would permanently derail the effort to build a new modern freestanding high altar in the transept of Notre Dame for at least a century.

First, the War of the Spanish Succession, which had broken out in 1701, placed a severe strain on the finances of the French King. This resulted in a delay to the construction of the new freestanding altar.

Then, as the delay dragged on into years, some of the canons of Notre Dame Cathedral began to grow uneasy about moving the altar to the transept. As described by historian Jean-Pierre Cartier, the king was increasingly subjected to “pressure from the most conservative canons” about the altar and ultimately backed down.

The refusal of the canons to permit the altar to be relocated was surprising and even shocking to some at the time. Abbot Jean-Louis de Cordemoy, writing in 1714 in his Nouveau traité de toute l’architecture, said:

“This is also what has made it difficult for the world to understand the reasons why the Canons of Notre-Dame of Paris did not consent to the new altar that the King is now having constructed there being placed in the middle of the crossing [transept]. But since this body is august and composed of wise and distinguished persons, one presumes that they have very good reasons.”

At that time in France there were some clerics who strongly objected to the Tridentine developments and Baroque architectural trends, specifically with respect to altars – chief among them the formidable liturgist and historian Jean-Baptiste Thiers.

The canons (with respect to the proposals for Notre Dame) and Thiers (more generally) resisted the modern elaborate altar designs of their day – as well as the post-Tridentine architectural trends which sought to “Romanize” and standardize sanctuaries and altars – on the grounds that these things were antithetical to the spirit and practice of liturgy in the early Church.

In his famous treatise on church altars, Thiers noted the diversity of traditions and historical practices regarding altar placement and pleaded in favor of respecting local architectural usages, rather than forcibly renovating and standardizing everything in the new modern fashion.

On the other hand, Cordemoy and those who strongly supported such freestanding altars and post-Tridentine sanctuary renovations also claimed that these developments were “happily returning to ancient usage.”

Both sides of this charged liturgical debate in the late 17th and early 18th centuries thus invoked claims about the practice of the primitive church to support their preferred liturgical and architectural preferences.

After this rejection by the canons, and with the French state still mired in financial straits, the original plans for the project were abandoned.

Robert de Cotte, who succeeded Mansard as the king’s architect, developed new plans for the project which eliminated the baldachin and kept the high altar in its traditional location in the sanctuary at the far end of the apse.

Five years later, in 1708, Canon Antoine de La Porte made an extraordinary financial gift to the king to allow the work on Notre Dame to proceed. By 1727, work was finally completed on a new high altar which met the original criteria of the vow. After almost a century, the Vow of Louis XIII was finally fulfilled.

“Pompes Funèbres”

In addition to the emphasis on visibility and accessibility with regard to liturgical action, there was another important liturgical and cultural trend that developed in the 17th century which would also influence the development of freestanding altars at Notre Dame Cathedral: the development of what are known as pompes funèbres or “funeral pomps.”

This phrase refers to elaborate state-sponsored ceremonies for major funerals which involved the construction of extravagant temporary altars, canopies, artistic decorations, scaffolding and seating structures, catalaques, and other things within the main nave of Notre Dame and other major churches.

Such grandiose funeral rites did not originate in France.

By the first half of the 17th century, splendid funeral monuments and ever-more-elaborate decorations and ceremonies were common at the courts of Catholic monarchs throughout Europe, except for France.

Jesuit scholar Claude-François Ménestrier helped to popularize and promote these “décorations funèbres” with the French monarchy and collaborated on them with members of the Menus-Plaisirs du Roi, a service of the royal household responsible for organizing and designing various ceremonies and spectacles.

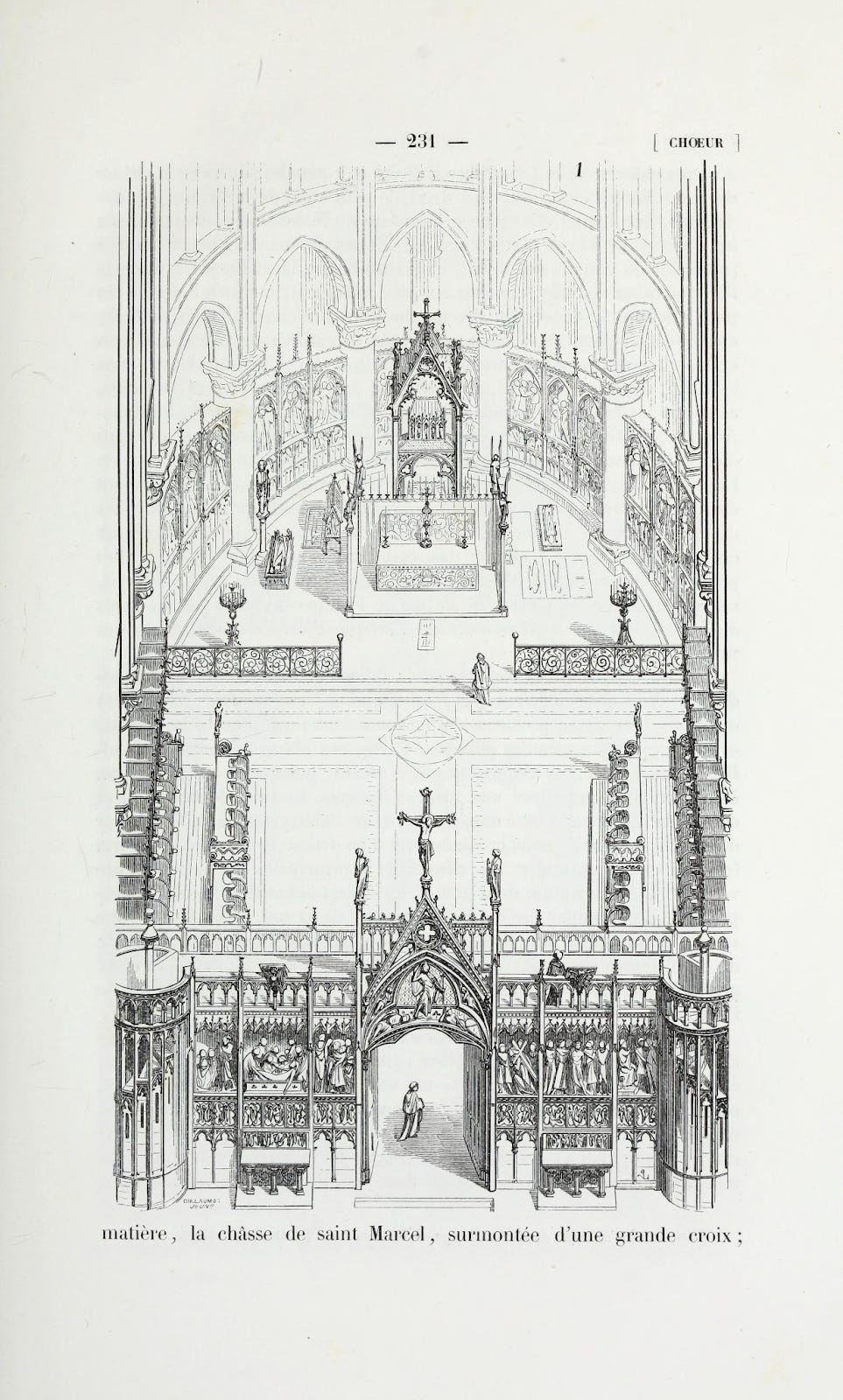

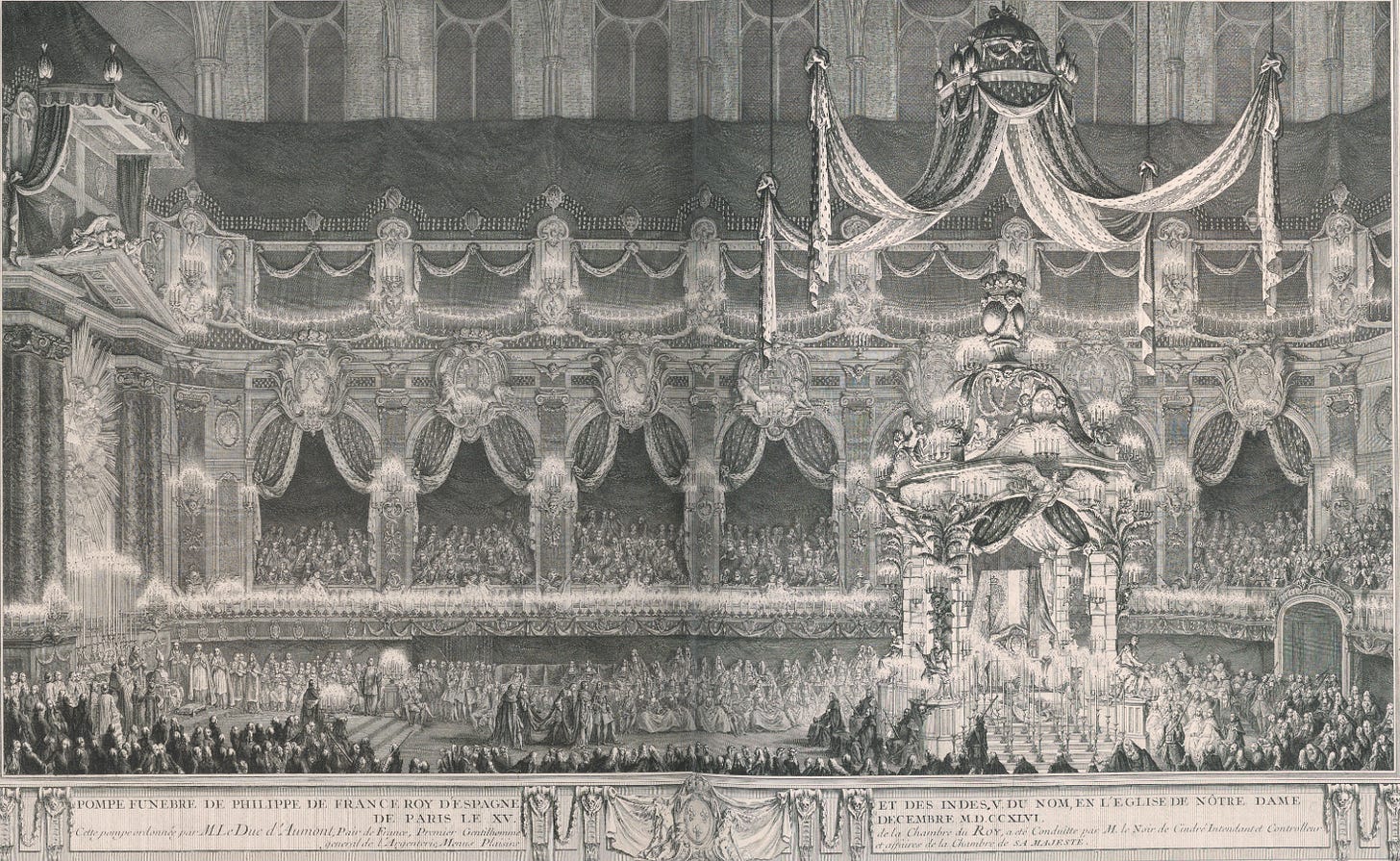

The year 1670 marked the first time that pompes funèbres were employed within Notre-Dame Cathedral, when a massive catafalque and funeral monument was erected in the choir for the funeral of François de Vendôme, duc de Beaufort.

A few years later, even grander pompes funèbres were constructed within Notre-Dame Cathedral for the grand state funeral of Turenne (Henri de La Tour d’Auvergne), the Grand Marshall of the king’s armies.

In the years which followed, increasingly more extravagant and creative pompes funèbres were developed by the Menus-Plaisirs department for particularly solemn or special funerals – like those of Louis II de Bourbon, Prince of Condé in 1687, Louis, Dauphin of France and Duke of Burgundy in 1712, Polyxene of Hesse-Rheinfels-Rotenburg in 1735, and King Philip V of Spain in 1746.

These grand funeral spectacles came to take the form of what could be described as a church-within-a-church.

For these events, the regular nave, choir, and high altar of Notre Dame were not used. Rather, a custom-built and elaborately decorated temporary chapel was constructed within the nave. This ceremonial chapel featured additional tiered seating, temporary high altars, grand funeral catafalques, and ornate hanging canopies.

This custom of constructing temporary altars and decorations within Notre Dame and other grand churches eventually expanded from only funeral ceremonies to other important events of state like royal baptisms, formal acts of thanksgiving, celebrations, and more.

While the temporary altars in the 1700s were not freestanding, they showed the architectural trends that were taking place in the centuries after the Council of Trent, with altars moved closer to the nave and a heavy emphasis on visibility and accessibility of the liturgical action of the Mass.

These trends, along with the memory of the almost-realized plan to construct a freestanding high altar in the transept of the cathedral, paved the way for the development of freestanding altars at the cathedral in the years to come.

This is the first in a two-part series exploring the origin and history of freestanding altars and versus populum Masses at Notre Dame Cathedral. The second part, which considers altar arrangements and liturgical celebrations at Notre Dame into the 20th century, can be found here.

This is interesting to read, but it doesn't make me like Notre Dame's freestanding new altar or its pre-fire predecessor any better. I will say that I have a slight preference for the plain half-moon shape over the "abstract evangelists" (shudder). But if Notre Dame now wants to use a "Mass Rock" as an altar, then it could have just skipped the design process and gone into the wilderness and found a big old rock beautifully designed by God the Creator, cleaned it up, and hauled it back to the Cathedral.

The image of the high altar with that cross standing tall in the ruins after the fire is the image that stays with me.

The aesthetics of the current altar aside, from a historiographical standpoint, I think that this is important work from the Pillar. There is a general understanding among Catholics who are "in the know" or "informed in tradition" that the liturgical experience offered precisely as it was prior to the reforms following Vatican II was simply settled.

That the declarations of St Pius V on the liturgy were interpreted during the time between Trent and Vatican II in the way which some traditionalist Catholics present them is taken as obvious truth. This is what irks me - that there can be no acceptance whatsoever that the 20th C reforms (regardless of their fruit and application) did not come out of thin air.

Can we ever get to a place where we can admit, from both side of the "aisle" that this has been an evolving reality over the centuries? That maybe, just maybe, we are not actually fixed in a dichotomy between the 1962 Missal and felt banner masses?

I don't mean to soften the blow to the soul that some of the liturgical abuses offer - only to say that a realistic understanding of the development of these seems to be the missing path out of the mess. The average parishioner/bishop/diocese seems likely to smell something "off" in the generally accepted (among the chronically online) notion that old=good and new=bad. There has to be more to the story.

Articles like this show just that to be the case.