What the Epstein emails said about the Vatican Bank

Was Epstein right about Vatican financial management?

The world’s media continues to digest the most recent release of data files by the U.S. Department of Justice relating to the case of Jeffrey Epstein, the convicted human trafficker and financier.

The so-called “Epstein files” continue to shed new light on the sprawling network of connections maintained by the man who pleaded guilty to child prostitution charges in the early 2000s and died in custody awaiting trial on a slew of similar and related charges.

Released caches of emails and documents have laid bare Epstein’s connections to and interests in a worldwide assortment of politicians, royalty, billionaires, trading notes with them on a range of subjects.

One exchange which caught the eye of Pillar readers, however, concerned the Institute for Works of Religion, colloquially called the Vatican Bank.

In a 2013 email following Pope Benedict XVI’s resignation announcement, Epstein told Larry Summers, the economist who served as director of the National Economic Council until 2011, and previously had worked as president of Harvard University and in the Clinton administration, that a change in leadership at the IOR may be “the most important change in the Vatican” — rather than the resignation of Pope Benedict XVI.

So what did Epstein say, and what did he mean? The Pillar explains.

What did Epstein’s email say?

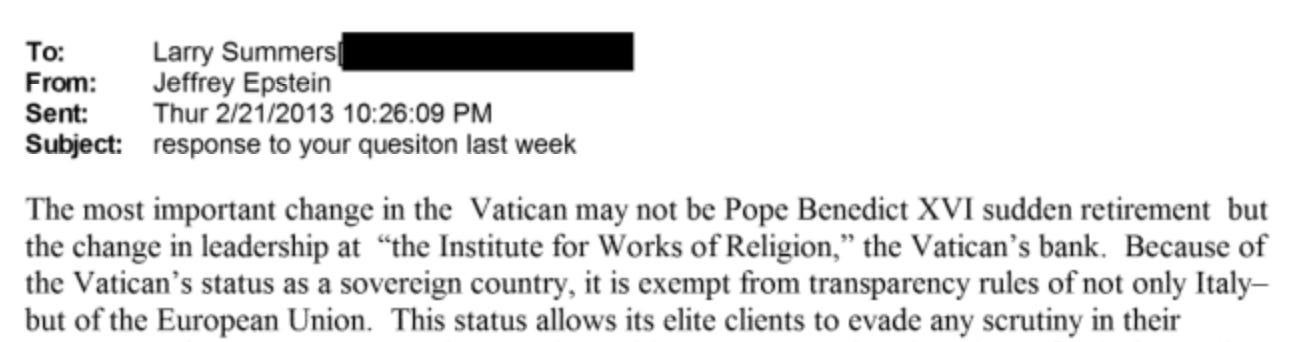

In an email dated Feb. 21, 2013, Epstein told Summers that “The most important change in the Vatican may not be Pope Benedict XVI sudden retirement but the change in leadership at ‘the Institute for Works of Religion,’ the Vatican’s bank.”

“Because of the Vatican’s status as a sovereign country, it is exempt from transparency rules of not only Italy— but of the European Union. This status allows its elite clients to evade any scrutiny in their money transfers,” Epstein wrote.

“Last May. Vatican Bank President Ettore Gotti Tedeschi was fired after Italian authorities opened an investigation into a far flung bribery scheme in which he was allegedly involved. Then 47 dossiers, including compromising about ‘internal enemies’ of his in the Vatican were found in a search of his home. They had instructions how they were used in case something happened to him. Tcdeschi’s [sic] intercepted calls futhcr [sic] revealed that his concern was that he would be assassinated because he knoew [sic] the Vatican’s secrets,” according to the email.

“By late 2012, he was cooperating with the ongoing Italian investigation. It was at this point that the all-powerful College of Cardinals, in one of the last acts in the Benedict papacy, appointed German lawyer Ernst von Freyberg as President of the bank. The came the extraordinary resignation of Pope Benedict [sic],” Epstein wrote.

Why did he write it?

The long answer is that the email was written the day after Pope Benedict XVI became the first pope in centuries to resign his office.

In his speech to the College of Cardinals, the pope said he had become increasingly aware that he did not consider himself up to the task of serving as pope as he grew older — he was 85 at the time.

Benedict’s resignation followed a series of corruption scandals in the Vatican, which collectively became known as “Vatileaks.” In response, the pope commissioned a task force of three cardinals to investigate curial corruption.

Cardinals Julián Herranz, Jozef Tomko, and Salvatore De Giorgi reportedly compiled several hundred pages of evidence and testimony which they presented to Benedict in December of 2012 and which many speculated contributed to the pope’s decision to resign.

According to Pope Francis, who succeeded Benedict in office in 2013, his predecessor delivered to him a “large white box” containing the cardinals’ report and supporting evidence in one of their first meetings after the 2013 conclave.

In his autobiography “Spera,” Francis said Benedict “gave me a large white box. ‘Everything is in here’, he told me. ‘Documents relating to the most difficult and painful situations. Cases of abuse, corruption, dark dealings, wrongdoings.’”

The IOR was often mentioned in and among the scandals and accusations of corruption throughout Benedict’s tenure as pope. In 2012, the bank’s president, Ettore Gotti Tedeschi, was removed from office by a vote of no-confidence from the board of superintendence. The week before Benedict announced his resignation, the board elected Ernst von Freyburg to serve as the bank’s new leader.

—

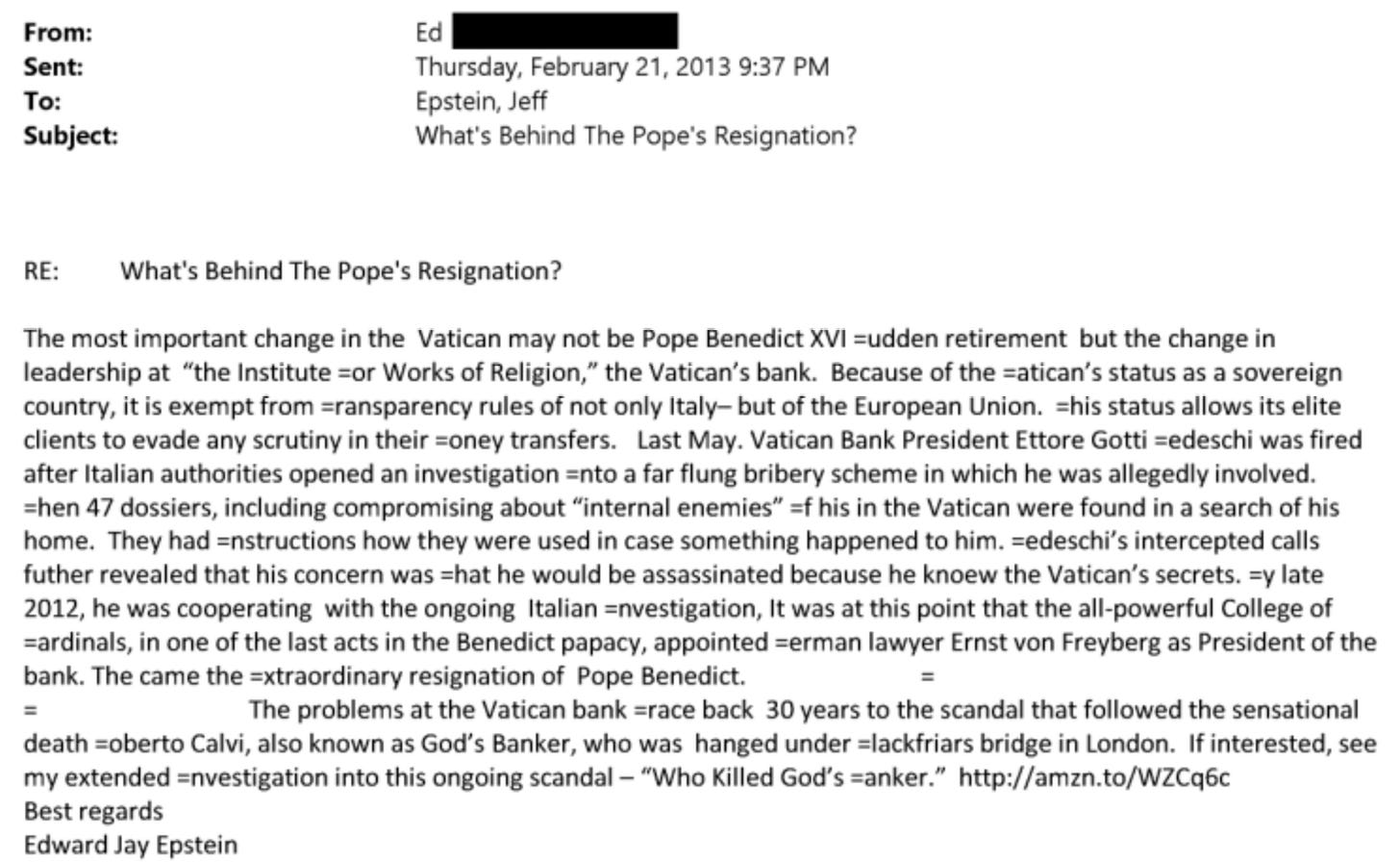

The short answer to the question of why Jeffrey Epstein wrote about those events to Larry Summer, though, would seem to be simpler: Because someone else wrote to him saying the same thing.

Also included in the DoJ releases is an email received by Jeffrey Epstein just an hour before his email to Summer — the contents of the two emails are, apart from pervasive typos, virtually identical — meaning Epstein essentially copied (and moderately edited for clarity) an email he received and sent it on to Summer as his own observations.

Confusingly, the email received by Jeffrey Epstein an hour before his email to Summer was sent by the journalist and Harvard professor Edward Jay Epstein, who concluded his email with a link to his previous coverage regarding the scandals of the IOR, including the Banco Ambrosiano affair.

OK — So did Epstein/Epstein have a point about the Vatican bank and the papal resignation?

In a word, no.

Despite Epstein’s assertion, there’s no serious way to argue that Erst von Freyburg’s appointment as president of the IOR was “the most important change in the Vatican” compared to Benedict’s resignation. But it’d be just as mistaken to think they had absolutely nothing to do with each other.

To be sure, financial corruption in the curia was a major issue during Benedict’s tenure, and serious Vatican analysts did maintain that the contents of the cardinals’ commission report played an important — some believe determinative — part in leading Benedict to resign.

And the IOR had been a locus of scandal for years, decades, even, because the Vatican City institution’s exemption from European banking regulations left it open to abuse for money laundering — in much the way the Epstein/Epstein emails outline.

However, during Benedict’s tenure, the IOR was already undergoing concerted reforming efforts, and it was in response to direct instructions from Benedict that the bank begin the process of conforming to external standards and achieve international “white list” status.

In fact, it was in June of 2012, after Tedeschi’s departure but because of actions undertaken during his tenure, that Moneyval, the European Commission’s anti-money laundering watchdog, was able to issue its first report on the IOR.

The emails indicate that Epstein (and Epstein) did not approach the IOR question with much grasp on the details — if for no other reason than they both claim that “that the all-powerful College of Cardinals, in one of the last acts in the Benedict papacy, appointed German lawyer Ernst von Freyberg as President of the bank.”

Calling the College of Cardinals “all powerful” as it relates to the IOR is something of a tell — the college is an advisory body to the pope, and it has nothing to do with the appointment of the IOR president.

But there must have been something going on, right? The president wasn’t fired for nothing, right?

Tedeschi’s ouster was, like so much involving Vatican finances, mired in allegations, claims and conspiracy theories — and the suggestion that he feared for his life and had compiled information on his supposed opponents is actually fairly close to the truth, though the extent to which Tedeschi was in any danger is open to debate, to say the least.

But it is fair to say the reasons for his removal in 2012 were hotly disputed, not least by the man himself, who claimed to be the victim of internal curial resistance to new regulation and transparency.

Others, like Epstein and Epstein, noted Tedeschi’s connection to Italian financial scandals — though he was never charged nor personally implicated in them, and was only ever identified as a potential witness. While the IOR continued to face money laundering allegations and investigations during his tenure, he was cleared of any wrongdoing.

According to Carl Anderson, then leader of the Knights of Columbus and a member of the IOR board, the 2012 vote to oust Tedeschi was the result of the banker’s lackluster work ethic — he apparently only came into the office twice a week — and “increasingly erratic personal behavior.”

So, the IOR is…?

As the only Vatican financial institution under external regulatory oversight, it has received a series of positive assessments from Moneyval, and operates at a level of transparency and external compliance other Vatican financial bodies can’t, don’t and won’t even consider.

In addition to ending permission for the personal and numbered accounts unrelated to Church entities and work — the accounts which led to allegations of money laundering in previous decades — the bank has posted a series of year-on-year profit notices.

The bank also reports annually on its Tier 1 capital ratio, an international standard measuring liquidity and institutional risk exposure for financial institutions. The minimum international banking requirement is a ratio of 6%. The ratio for larger U.S. banks is usually somewhere between 13% and 17%.

In 2024, the IOR had a Tier 1 ratio of 69.4%, up from 59.8% in 2023.

Far from being implicated in financial scandals, the current leadership of the bank, president Jean-Baptiste de Franssu and director Gianfranco Mammí, have actually proven to be key whistleblowers on curial financial matters.

In 2019, it was the IOR leadership who flagged — despite threats and offers of “protection” from other Vatican departments, including the Secretariat of State — the suspicious activity which led to the uncovering of the London property scandal and Vatican financial crimes trial which convicted nine people, including a cardinal, in 2023.

As a civil party to that case, the bank filed a claim for 1 million euros in reputational damages against the defendants, which include the former deputy head of the Secretariat of State, Cardinal Angelo Becciu.

Thanks for this reporting on the Vatican Bank, which required some plowing through lots of confusing information.

Many decades ago people would study books of great quotations to be able to say something witty at parties of the intellectual elite.

In the same vein, if you want to pass yourself off as some financial genius with deep insight into global finance, it is not at all surprising that you would pass someone else's thoughts/email off as your own. Particularly if you had no financial skill and deep knowledge.