Why does canon law tell dioceses to destroy their files?

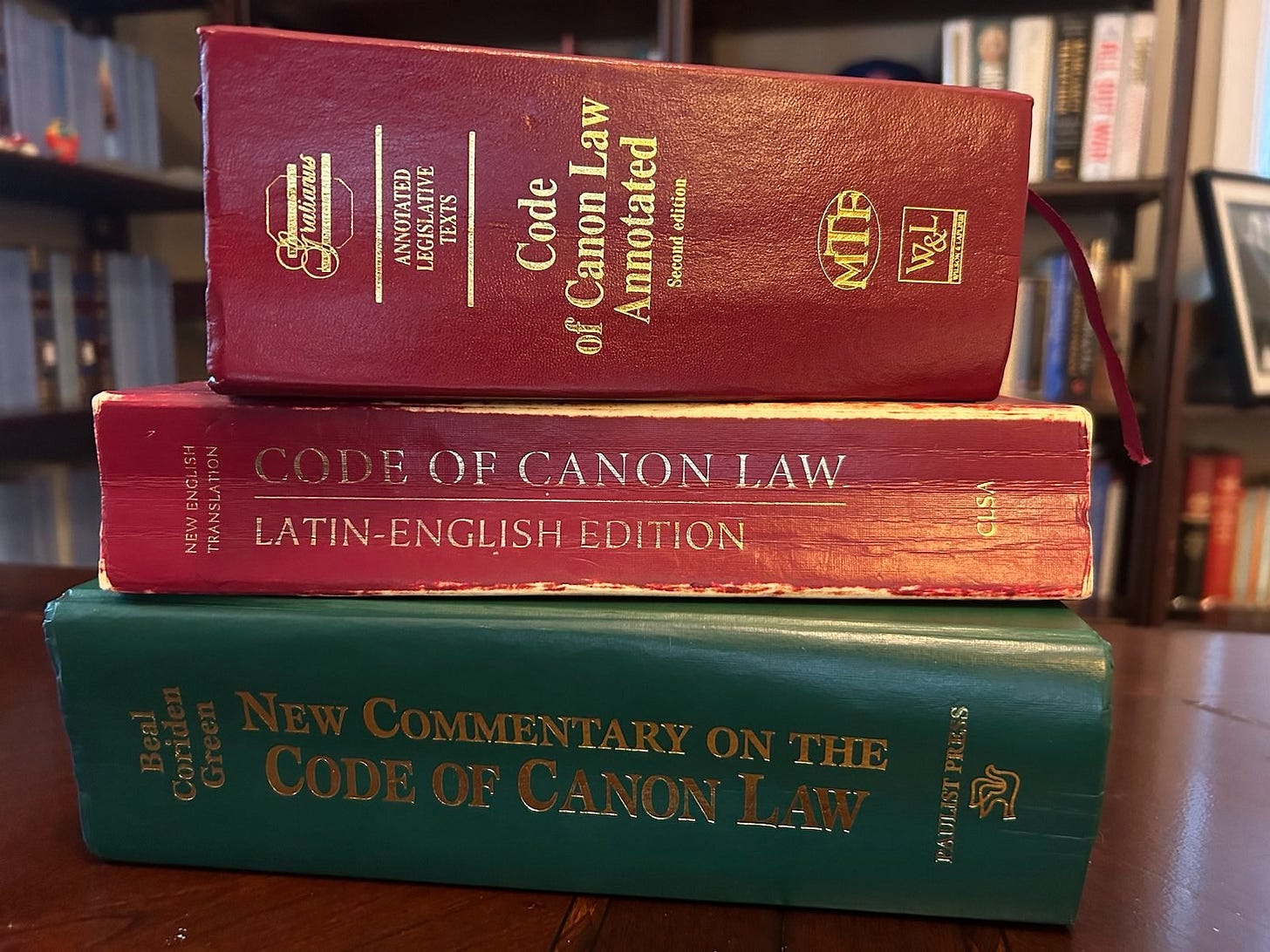

What does the Church’s law actually say about destroying records of abuse cases?

The bishops of Switzerland continue to wrestle with a crisis, triggered by the publication of a landmark independent report on clerical sexual abuse.