Will bishops thaw Weisenburger ICE proposal?

Amid national immigration controversy, might a long frozen question about canonical penalties be revived?

As the United States falls into deeper division over the Trump administration’s immigration enforcement mechanisms, bishops are beginning to speak out — with Cardinal Joseph Tobin this week calling Immigration and Customs Enforcement a “lawless organization” and urging that it be defunded.

And as momentum seems to build among bishops criticizing federal immigration actions, at least some observers will begin to ask whether a shelved episcopal proposal might come up for discussion again. If it does, will U.S. bishops find momentum building for a proposal mostly ignored when it first came under consideration?

—

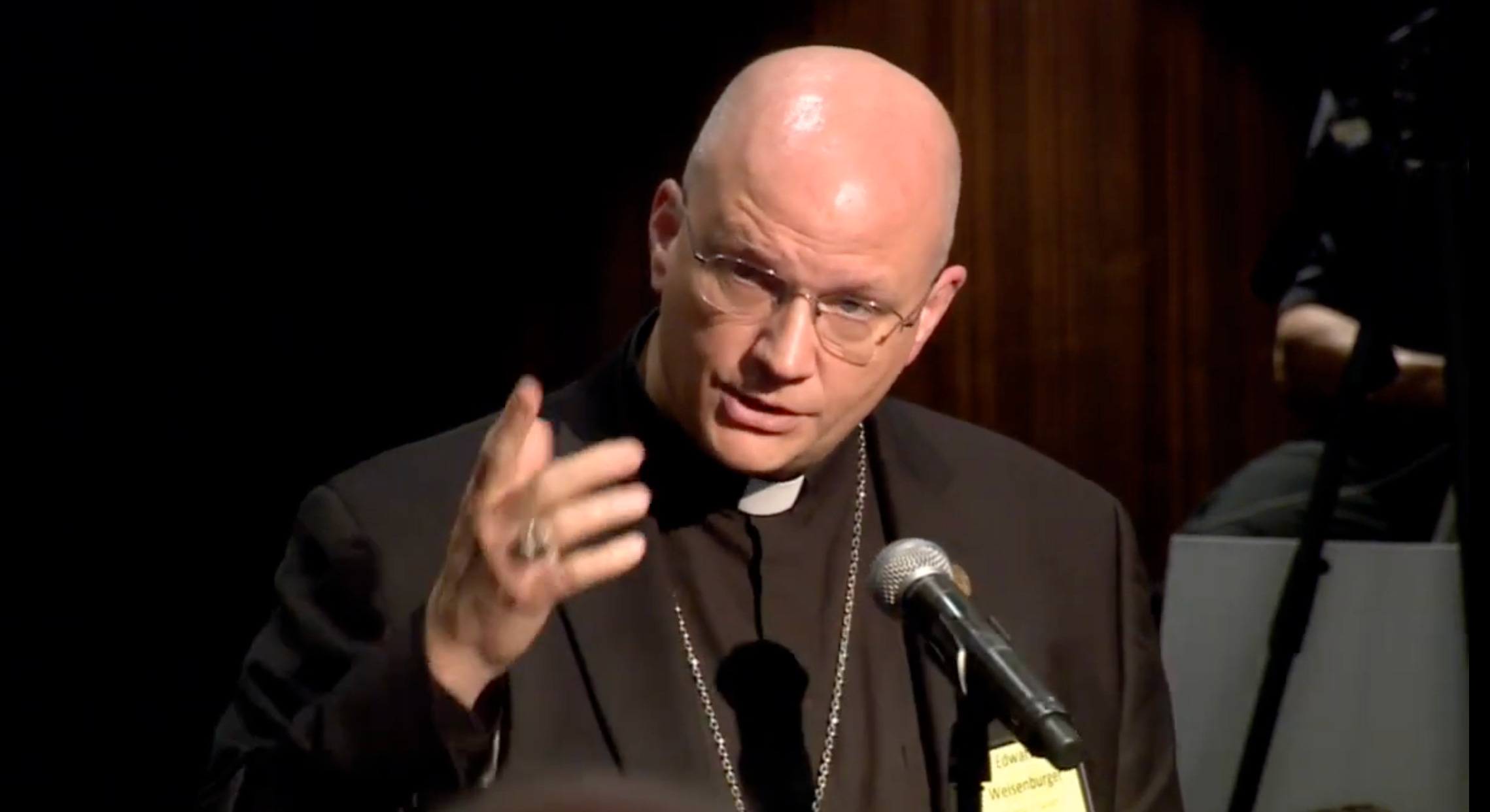

In June 2018, an Arizona bishop stood up at the June meeting of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops with a surprising idea.

The bishop led a diocese at the U.S. border, and bishops were discussing their concerns about the Trump administration’s restrictions on asylum qualification, announced intention of increased prosecution for people crossing the southern U.S. border illegally, and the emerging practice of separating children immigrating with parents from their families.

Unsurprisingly, the bishops’ concerns focused especially on family separation, and they discussed ways they might advocate for families facing the prospect of detention and separation.

At the start of the discussion, Texas’ Cardinal Daniel DiNardo said directly that “separating babies from their mothers is not the answer and is immoral,” adding that “families are the foundational element of our society and they must be able to stay together.”

For the most part, the discussion focused on a proposal from Cardinal Tobin, who thought the bishops’ conference should push for a cadre of bishops to inspect detention centers along the border, especially those housing minors, as a “sign of our pastoral concern and protest against the hardening of the American heart.”

But when Bishop Edward Weisenburger of Tucson stood, he changed the conversation.

“I have never been a canonist that wanted to rush in with a sledgehammer with penalties, I don’t think that reflects the canons well, or the theology behind them,” the bishop said.

“However, in light of the canonical penalties that are there for life issues, I’m simply asking the question if perhaps our canonical affairs committee could give recommendations at least to those of us who are border bishops, on the possibility of canonical penalties for Catholics involved in [family separation].”

“I think the time is there for a prophetic statement,” Weisenburger added.

The bishop understood that his idea might not take off — “what I’m saying may be a little risky or dangerous,” he told his brothers.

But he said his intention was for the pastoral work of conversion — “I think it’s important to point out that canonical penalties are put in place to heal — first and foremost to heal, and therefore, for the salvation of these people’s souls.”

In light of that, he said: “maybe it’s time for us to look at canonical penalties.”

—

No one among the U.S. bishops meeting in Fort Lauderdale in June 2018 could predict what the next eight years would hold for the Church.

Soon after that meeting, the scandal of Theodore McCarrick broke, and the Church grappled with that for the next few years, as the pandemic eventually took national attention, deepened division in America, and contributed to the radical shift in American public life and political culture that feels to most observers like the beginning of a very different — and darker — chapter in the American story.

Amid all of that, the Weisenburger proposal got almost no ecclesiastical discussion after it was floated in June 2018, save for the news cycle of headlines it prompted, and a bit of pushback from Catholics who thought it trivialized the Church’s response to abortion.

But as bishops push back on the Trump administration’s immigration enforcement mechanisms this week, and especially on the growing perception of police brutality on the part of ICE agents, it’s possible to consider that Weisenburger’s question might be taken up by the U.S. bishops for consideration again.

—

In recent weeks, several U.S. bishops have spoken out to criticize the Trump administration more directly than they have previously.

Archbishop Timothy Broglio told a journalist earlier this month that a possible military incursion into Greenland — floated as a real possibility by the Trump administration — would not meet the criteria for a just war, and that it would be “morally acceptable” for military members to disobey orders for a military operation to take control of Greenland.

Three U.S. cardinals — Cardinals Tobin, Robert McElroy, and Blase Cupich — soon after that issued a decisive and broad criticism of the Trump administration’s foreign policy initiatives, including Greenland, alongside a host of other issues.

Broglio and those cardinals are not often on the same side of the ecclesiastical aisle. But their remarks come as bishops have already shown unusually unanimous resolve to oppose the administration’s deportation agenda. That resolve was shown in an extraordinary statement issued by the bishops’ conference in November, followed up by a video presentation of the statement featuring dozens of U.S. bishops — seemingly chosen for the video for the broad range of ecclesiastical perspectives they represent.

The commitment was more than verbal, and soon after saw even bishops with reputations as theological “conservatives” leading prayer vigils outside of ICE detention centers.

That was the context in which Tobin told faith leaders on a Jan. 25 national call — which came the day after the killing of Alex Pretti, a Minneapolis Catholic detained, disarmed, and then shot by federal agents after he attempted to assist a woman who had been shoved down at a protest — that lawmakers, “for the love of God and the love of human beings … [should] vote against funding for such a lawless organization.”

Referencing Pretti’s death, the shooting death of Renee Good, and Jan. 20 detention of a 5-year-old taken into custody after returning from school, the cardinal said that he “mourn[s] for a world that allows 5-year-olds to be legally kidnapped and protesters to be slaughtered.”

The language was sharp and direct, it took without hesitation or reservation a clear perspective on federal activity in Minneapolis. Most notably, as Tobin mentioned ICE activity in Minnesota and in detention centers with which he had experience, the cardinal imputed blame not to particular individuals, but to the agency in the aggregate, on the whole, which he regarded as “lawless.”

While some bishops have struck a more conciliatory tone toward the Trump administration than Tobin, no prelates have challenged his characterization of ICE. And in fact, few seem likely to — the government’s immigration enforcement efforts have increasingly fewer defenders, as the Minnesota events have seemed to begin shifting public opinion on ICE’s methods.

Critics of the bishops have long questioned the sincerity of their advocacy over immigration issues, echoing charges by Vice President JD Vance that the bishops’ immigration stance is colored by the grants they’ve administered to Catholic Charities organizations for refugee resettlement work.

While the bishops’ conference has rejected those criticisms, there is evidence that a loss of its own administrative fees for refugee work has contributed to financial challenges for the USCCB, including at least some contribution to the fiscal challenge of maintaining its Washington, D.C. headquarters, which could eventually be sold.

But whether or not that has contributed to the bishops’ rhetoric on immigration, one thing seems clear in recent months — the Overton window on episcopal rhetoric on Trump has shifted among the bishops. And in that context, it does not seem unreasonable to expect that some prelate — perhaps Weisenburger himself — will either dust off the 2018 proposal for discussion, or attempt some iteration of it in his diocese.

Of course, when it comes to canon law, the details matter.

When Weisenburger spoke of “canonical penalties” in 2018, he seemingly did not mean a formal penalty at all, issued after a canonical trial for some specific canonical crime. Instead, he seemingly was referring colloquially to the prudential application of canon 915, which prohibits the administration of the Eucharist to Catholics who “obstinately persevere in manifest grave sin.”

That canon’s application to pro-abortion politicians was roundly debated in 2020 and 2021 by the bishops, leading to a document which emphasized that “lay people who exercise some form of public authority have a special responsibility to form their consciences in accord with the Church’s faith and the moral law, and to serve the human family by upholding human life and dignity,” and that:

“If a Catholic in his or her personal or professional life were knowingly and obstinately to reject the defined doctrines of the Church, or knowingly and obstinately to repudiate her definitive teaching on moral issues, however, he or she would seriously diminish his or her communion with the Church. Reception of Holy Communion in such a situation would not accord with the nature of the Eucharistic celebration, so that he or she should refrain.”

Drawing from canon 915 and the debate over politicians, the bishops added that “it is the special responsibility of the diocesan bishop to work to remedy situations that involve public actions at variance with the visible communion of the Church and the moral law. Indeed, he must guard the integrity of the sacrament, the visible communion of the Church, and the salvation of souls.”

Applying those norms and resolutions to politicians advocating for abortion-permissive laws is generally seen as straightforward. If a legislator has a record of voting to advance such laws, he might be warned by his bishop, and if he continues along the same trajectory, he might be formally declared prohibited from reception of the Eucharist unless he repents from his support for abortion’s legal protection.

Applying the same norm to federal agents seems less canonically clear.

Most straightforward is that if the bishops decided that particular bills or executive orders or even operational orders or approaches were manifestly grave sin, they could formally warn directly those responsible for carrying them out, and, barring unexpected contrition, proceed from there.

But as to the rank-and-file membership of a federal agency, a bishop would likely find it far more controversial to declare that continued employment constituted de facto manifest grave sin — but if he did, would be responsible to personally warn those individual members under his jurisdiction who might be individually prohibited from the reception of the Eucharist.

That approach seems improbable.

There is another unlikely canonical avenue which might well be floated in light of Weisenburger’s questions about canonical penalties — namely, the application of an interdict on ICE itself, an effective declaration that the organization, being “lawless” is not suitable for Catholic participation, and that Catholics employed by ICE must seek other employment or be prohibited from sacramental and other kinds of participation in the Church’s life.

Obviously, on first glance that approach might seem entirely improbable — it would be an unusual direct act of authority in contemporary ecclesiastical life, to say nothing of the controversy and division it would generate.

And specificity seems all the more difficult. While federal immigration surge tactics are generally spoken of under the general moniker of ICE operations, they tend to actually involve agents from several interconnected agencies: Reports indicate that Pretti was shot by agents from the federal Border Patrol and Customs and Border Protection agencies.

But, surprisingly, the idea is not actually lacking contemporary precedent.

It is worth noting that a bishop in Germany seems to have effected in recent years a kind of de facto partial interdict on membership — or at least leadership — in the Alternative for Germany party, prohibiting in 2024 a state lawmaker belonging to the party from participation in a parish council.

The AfD party has been criticized in Germany by the country’s bishops’ conference, for a “racial-nationalist attitude,” with the conference saying the party’s “dissemination of right-wing extremist slogans — including racism and anti-Semitism in particular — is incompatible with professional or voluntary service in the Church.”

Notably, at the time of his prohibition, the Diocese of Trier acknowledged that the lawmaker — Christoph Schaufert — had not himself offered any “extremist opinions,” or “explicitly anti-constitutional or anti-Semitic statements” in his role on the parish council.

Instead, his membership in the organization was itself enough to disqualify him:

“Even if he does not position himself publicly in a way that can be criticized, it remains the case that he is a representative of a party that represents attitudes that contradict the Christian view of humanity — and that he does not distance himself from this,” Trier’s vicar general said in 2024.

The Vatican’s Dicastery for Clergy upheld that prohibition this month.

In light of that precedent, it does not seem altogether far-fetched to imagine an American bishop — as the tide against ICE enforcement tactics continues to build — might make a similar decision for ICE agents in his own diocese. While ICE is not a political party, condemnations like Tobin’s seem to have set the stage for that possibility.

Of course, the fallout for such a decision would likely be immense in the U.S., with a protracted disagreement among Catholics which would likely dwarf the rancor of the original Eucharistic coherence debate — especially if bishops pushing now for some canonical action or resolution were the same ones opposed to that idea during the Eucharistic coherence fracas of just four years ago. That reality probably means that discussion would go no further than that.

But as the rhetoric ratchets up, the outer limits of episcopal discourse will continue to shift — and eventually new fault lines will begin to show.

Presently, the conference itself is urging peace, both in the country and among Catholics — with conference president Archbishop Paul Coakley urging Wednesday a “Holy Hour for Peace” in every U.S. diocese.

Coakley urged Catholics to “ask the Lord to make us instruments of his peace and witnesses to the inherent dignity of every person.”

Whether that peace can hold, even among bishops, remains to be seen.

The Supreme Court not only allowed, but mandated, legal abortion on demand nationwide for 50 years, resulting in tens of millions of deaths. The Supreme Court was not placed under interdict.

The Department of Health and Human Services repeatedly sued nuns for years trying to force them to pay for birth control and abortifacient pills. DHHS was not placed under interdict.

The Food and Drug Administration green-lighted abortion pills that directly kill hundreds of thousands of innocent human beings every year. Then they allowed them to be prescribed via telehealth to make it easier. Now they have approved a generic version to make it cheaper. The FDA has not been placed under interdict.

I guarantee you if the Bishops did this as a body they would lose what little legitimacy is left in the USCCB.