The Altars of St. Mary’s – Part 2

A history of freestanding altars & Mass facing the people at Notre-Dame de Paris

This is the second in a two-part series exploring the origin and history of freestanding altars and versus populum Masses at Notre Dame Cathedral. The first part, which considers liturgical and architectural developments at Notre Dame between the 17th and 19th centuries, can be found here.

By the late 1700s, Notre Dame Cathedral was accustomed to the periodic construction of elaborate temporary altars and ceremonial decorations on the occasions of important funerals at the cathedral.

While the altars at that time were not freestanding, they demonstrated the architectural trends that were taking place in the centuries after the Council of Trent, with altars moved closer to the nave and a heavy emphasis on visibility and accessibility of the liturgical action of the Mass.

These trends would pave the way for the use of freestanding altars in the transept of the cathedral in the years that followed – as well as the regular, public, and uncontroversial practice of Mass facing the people by churchmen of the highest ecclesiastical offices, decades before the Second Vatican Council.

Revolution

The year 1789 marked the onset of radical political and social upheaval in France, following King Louis XVI’s convocation of the Estates General and ensuing developments that kickstarted the French Revolution.

In early 1790, the new French National Assembly was engaged in work to develop a constitution, sweep away the old order, and completely transform almost every aspect of life in France – including the legal code, social organization, and religion.

On Feb. 4, 1790, in a move which shocked almost everyone, King Louis presented himself at the assembly in person and gave a historic speech in which he recognized the legitimacy of the assembly, committed himself to reform, and pledged that he would uphold the forthcoming national constitution.

Ten days later, a grand civic and religious spectacle was organized to celebrate the king’s landmark speech and promises. On Feb. 14, 1790, the three main political and revolutionary entities in Paris – the National Assembly, the Paris Commune, and the National Guard – made a solemn procession to Notre Dame Cathedral to swear a civic oath.

The interior of the cathedral had been transformed for this occasion (an illustration of the scene can be viewed here)

A curtain had been hung over the entrance to the choir, blocking off a view of chancel and high altar. The flags of the 60 battalions of the National Guard lined the length of the nave.

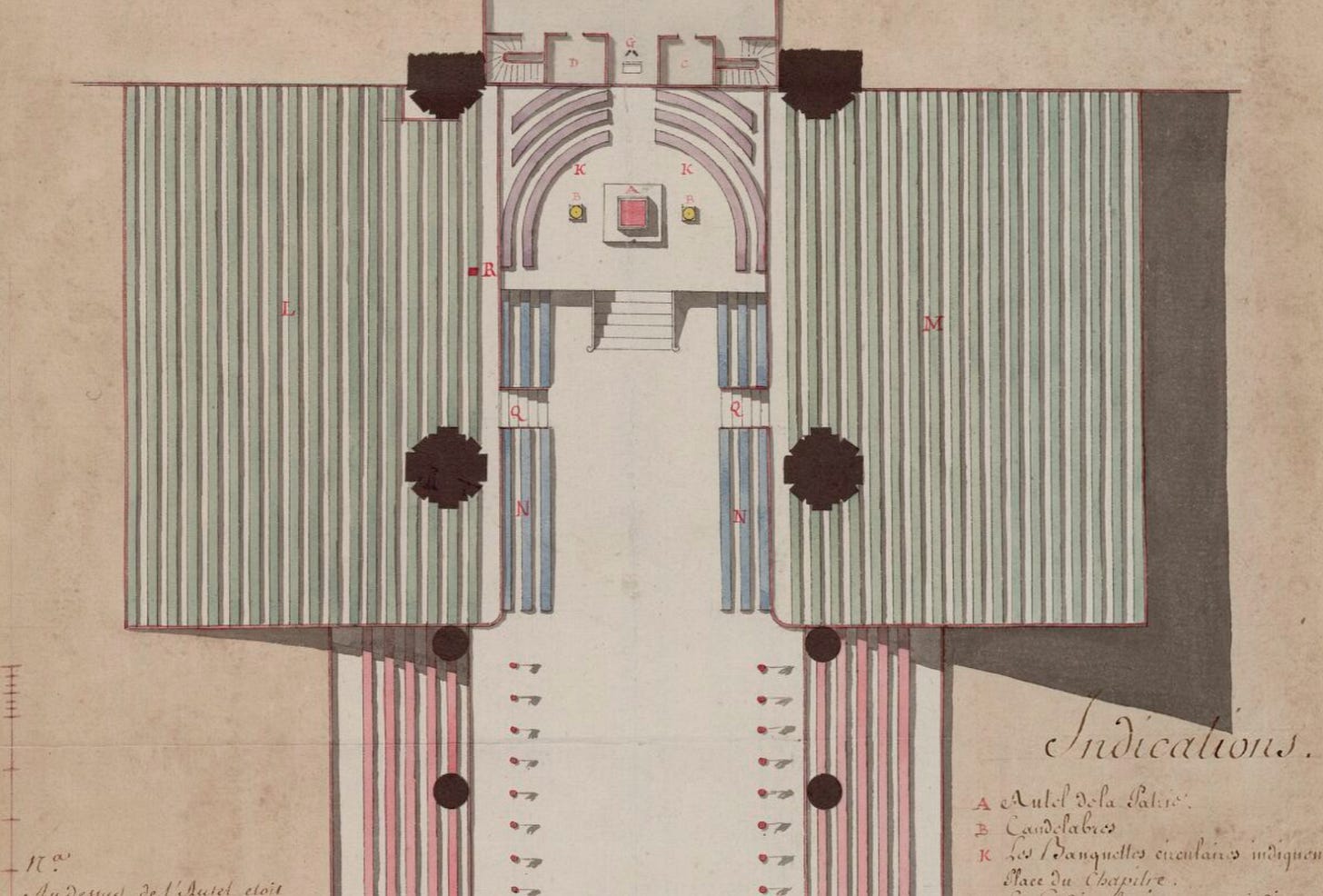

A large freestanding altar (dubbed the “altar of the fatherland”) had been erected in the transept, surrounded by benches and tiered seating designated for the various members of the assembly, commune, dignitaries, and members of the general public.

This seems to have been the first time, since the aborted plan for a new high altar under King Louis XIV, that a freestanding altar had been erected in the transept of Notre Dame.

The ceremony began with a Mass offered by Father Louis-Pierre Saint-Martin, chaplain of the National Guard. This was followed by a discourse given by Father François-Valentin Mulot which attempted to synthesize and bless the work of the revolution, the constitution, and the king, and to encourage everyone to embrace the civic oath.

Mayor of Paris Jean Sylvain Bailly then swore the oath in front of the altar – “to be faithful to the nation, to the law, and to the king, and to uphold with all my power the Constitution decreed by the National Assembly and accepted by the king” – which was then followed by everyone else in the cathedral.

The entire ceremony concluded with a grand rendition of the ancient hymn of thanksgiving Te Deum and the Domine, salvum fac regem (Lord, save the King), led by the cathedral chapter and musicians.

But this moment of potential civic peace and coexistence with the revolution was not to last – neither for the king nor for the cathedral.

Following the execution of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette in 1793, the secular revolutionaries – instigated primarily by Maximilien Robespierre – desecrated Notre Dame and converted it into a “Temple of Reason” for use by the deistic Cult of the Supreme Being.

Shortly afterwards, Catholic worship was forbidden in Paris. Notre Dame was turned into a wine warehouse for the French army, put up for auction, and designated for eventual demolition.

Robespierre’s fall from power in July 1794 saved the cathedral from an untimely demise. Just over a year later, in August 1795, the celebration of Mass returned to the cathedral, which by that point was in dire condition – windows shattered, full of rubble and ruins, and still storing a sizable number of the army’s wine casks.

The physical and religious situation of Notre Dame began to improve after Napoleon Bonaparte overthrew the revolutionary government in 1799 and signed the Concordat of 1801 with Pope Pius VII.

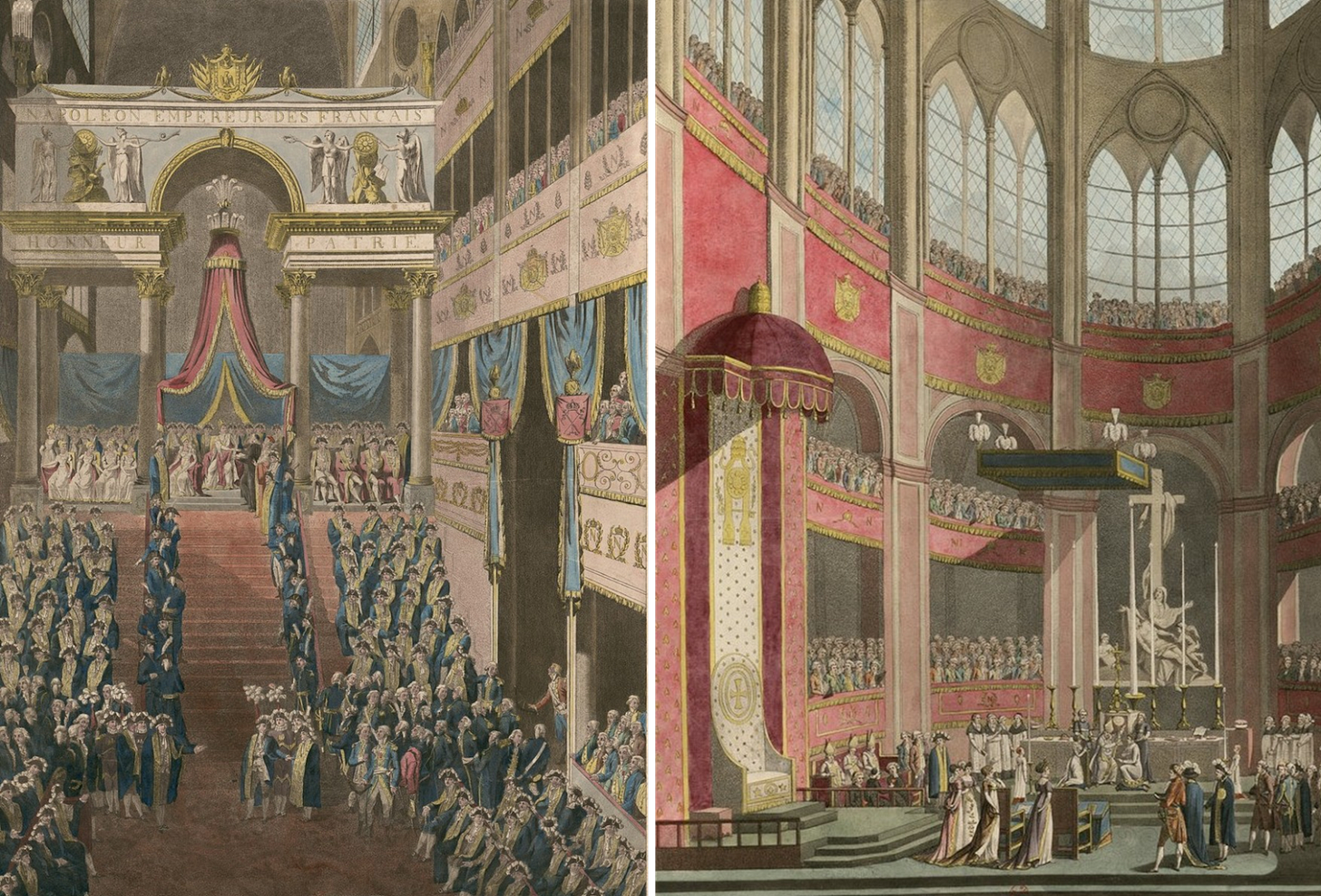

Some initial repairs to the building were undertaken and the cathedral was extravagantly decorated and transformed – in a way that strongly recalled the previous pompes funèbres customs – for the occasion of Napoleon’s imperial coronation on Dec. 2, 1804.

An elevated decorative arch – with thrones for Napoleon, his wife Josephine, and the pope – was erected in the west end of the nave, near the organ and main rose window. The building was filled with scaffold seating and other decorations, and the choir, sanctuary and high altar were also modified for the occasion.

After Napoleon’s final defeat in 1815, the French monarchy was restored and King Louis XVIII ascended to the throne. Louis had no children and there was concern within the Bourbon royal family about the line of succession and the lack of male heirs.

In 1821 Louis’ brother, Charles Philippe (who would become king in 1824 after the death of Louis), welcomed the birth of a male grandchild. The boy was named Henri, Count of Chambord and Duke of Bordeaux. This was a moment of extraordinary joy for Louis and the royal dynasty. A grand celebration was therefore arranged at Notre Dame Cathedral for the child’s baptism.

Henri’s baptism took place on May 1, 1821. Notre Dame was lavishly decorated with temporary structures, again recalling the former pompes funèbres traditions. On this occasion, a large freestanding altar under a baldachin was erected in front of the entrance to the choir – something that hearkened back to the unrealized proposal to move the high altar to that spot under Louis XIV in 1701.

This ceremony marked the beginning of a new chapter in the history of liturgical practice at Notre Dame. Following Henri’s baptism, the practice of using freestanding altars in the transept during important celebrations would grow increasingly more common over the following century.

The traditional high altar in the sanctuary was still regularly used. But freestanding altars were regularly employed on special occasions at Notre Dame, like the baptism of the Comte de Paris on May 2, 1841, or the baptism of Louis-Napoléon, Prince Imperial on June 14, 1856.

By the turn of the 20th century, the practice of using freestanding altars in Notre Dame – particularly on important ecclesiastical occasions, like the ordination of bishops – became increasingly commonplace.

For example, on Sept. 8, 1915, Léon-Adolphe Lenfant was consecrated as the Bishop of the Diocese of Digne. According to Laurent Prades, heritage director of Notre Dame, this was conducted “on a large platform that had been erected in front of the choir screen between the two transepts.”

Similar arrangements were used for episcopal ordinations in the years which followed. The most common arrangement seems to have been a raised wooden platform which served as a type of bridge between the entrance to the choir and the transept, through the space that had once been occupied by the rood screen.

This was done, for example, during the consecration of Alfred Baudrillart as auxiliary bishop of Paris on Oct. 28, 1921 and the consecration of Jules-Marie-Victor Courcoux as bishop of Orléans on 18 Jan. 18, 1927.

In this way, it seems that the custom of utilizing temporary altars gradually transitioned from something done for grand occasions of state to more regular and even perhaps semi-permanent use at Notre Dame by the early 20th century.

Facing the people

In November 1929, Jean Verdier, then-vicar general of the diocese, was appointed as the new archbishop of Paris. Within a month, Verdier had been both ordained a bishop by Pope Pius XI in the Sistine Chapel and made a cardinal.

Verdier would become a colossal figure within the Catholic Church in France during the course of his episcopate, and he initiated several significant pastoral initiatives within a year of his appointment.

In December 1930, one such initiative made its mark on Notre Dame: using a freestanding altar in the transept to offer Mass versus populum (facing the people). As described in the Liturgical Movement journal Orate Fratres:

“Cardinal Verdier, archbishop of Paris, has given orders that henceforth, on the occasion of pontifical ceremonies in the metropolitan cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris, a temporary altar will be prepared at the cross-section of the grand nave and the transept so that it will be in better view of the faithful …

“As the Blessed Sacrament is not to be reserved on the temporary altar and no tabernacle is necessary, the altar will be placed in such a position that the celebrant faces the congregation throughout the Mass. For this reason he will not have to turn about when chanting the Pax vobis, the Orate fratres and the Ite missa est.

“The innovation was tried out at Christmas and pronounced a great success, giving full satisfaction to the people and at the same time preserving the majesty of the ceremony.”

Verdier had performed his theological studies in Rome, and had been impressed by the unique liturgical orientation of the altars in the major Roman basilicas, which allowed the priest to face the people. This was part of the reason he ordered this arrangement in Notre Dame, to create an altar which he frequently described as “a la romaine—according to the Roman usage.”

Verdier regularly offered Mass in this way at his cathedral of Notre Dame for the high feasts and great ceremonies throughout the liturgical year, which in turn influenced other churchmen – archbishops and cardinals – to do the same.

For example, there are contemporary reports that Cardinal Jean-Marie-Rodrigue Villeneuve, Archbishop of Quebec, was greatly moved to celebrate Mass while facing the people at Notre Dame. Villeneuve would permit similar celebrations in the Archdiocese of Quebec and also celebrated them himself, as he did for example in August 1939 at the Basilica of Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré.

Verdier invited Vatican Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli (who would later become Pope Pius XII) to offer Mass in Notre Dame on July 13, 1937. A pontifical throne was erected in front of the traditional high altar, and this Mass was also offered on the freestanding altar while facing the people.

Pacelli’s homily on this occasion paid homage to the illustrious history of the cathedral and its status as a treasure and inspiration to Catholic France and the world.

–

Cardinal Emmanuel Suhard succeeded Verdier as Archbishop of Paris in 1940 and continued the tradition of regularly offering Mass facing the people from an altar in the transept throughout his episcopate until his death in 1949.

Following the end of the Second World War, France entered a period known as the Trente Glorieuses – the Thirty Glorious Years – a period of notable economic growth, prosperity, and vitality beginning around 1950.

These wider social and cultural trends were in some ways reflected in the liturgical developments and architecture of Notre Dame under Cardinal Maurice Feltin, who succeeded Suhard in 1949.

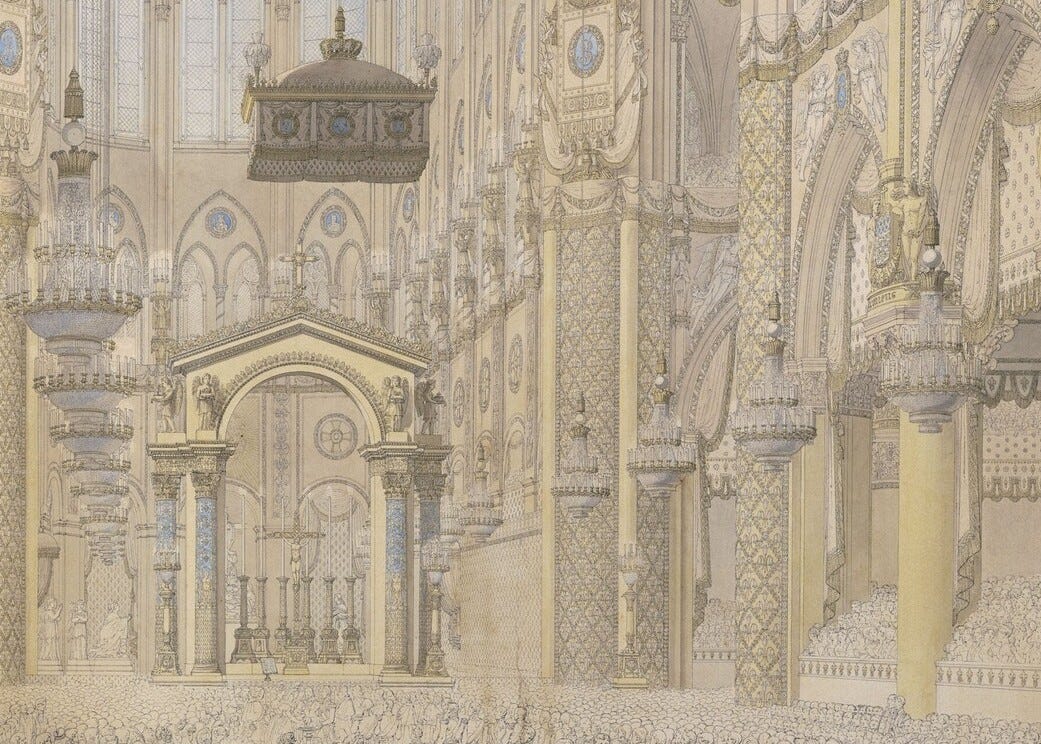

In the 1950s, the freestanding altar in the transept was no longer merely used occasionally for grand episcopal functions. A permanent elevated platform with a permanent freestanding altar had been constructed, and would remain in constant use over the next several decades.

Under Feltin, the Catholic Church in France boldly embraced the technological and social transformation of those glorious years through innovative national Catholic television broadcasts. This included the creation of a weekly Catholic television show Le Jour du Seigneur (the Lord’s Day) and the use of regularly televised Masses for the modern TV-watching populace.

By 1954, televised Masses had become such a widespread phenomenon that an international conference was held in Paris to discuss the topic. Hosted by the International Catholic Association for Radio and Television (UNDA), the conference concluded with a televised Mass from the royal chapel of Versailles.

In December of that same year, Feltin organized a spectacular televised Christmas Midnight Mass from Notre Dame.

The elaborate production was broadcast by a joint effort of eight major European television networks and was viewed by millions of people throughout Europe to high praise – the London Sunday Times praised it as “one of the outstanding television broadcasts of this or any other year.”

The French magazine Télérama described the preparations for the grand celebration, which included six cameras and eight commentators.

Versus populum spreads

The regular celebration of Mass facing the people on a freestanding altar was not only taking place at Notre Dame in the decades before the Second Vatican Council. Rather, it was public, prominent, uncontroversial, and even broadcast as a praiseworthy example throughout Western Europe.

The first 20th century experiments with using a freestanding altar to offer Mass versus populum seem to have occurred at the Benedictine Abbey of Maria Laach in Germany, an epicenter of the Liturgical Movement, in August 1921.

After visiting the abbey and observing the practice, Bishop of Trier Anton Mönch decided to occasionally celebrate Mass in this way – as he did, for example, during his diocesan Eucharistic Congress in 1922.

The practice of offering Mass while facing the people spread fairly quickly throughout Germany and became a regular feature of diocesan and national Catholic festivals.

Eugenio Pacelli, during his tenure as Apostolic Nuncio to Germany, personally celebrated Mass versus populum on grand outdoor freestanding altars for massive crowds at the annual Catholic Congresses – known as ‘Katholikentag’ – throughout Germany: 1924 in Hannover, 1925 in Stuttgart, 1926 in Breslau (now Wrocław), 1927 in Dortmund, 1928 in Magdeburg, and 1929 in Freiburg.

Openness to, and support for, versus populum Masses on the part of bishops and cardinals around the world increased as the 1920s gave way to the 1930s.

In 1929, Bishop Johannes Aengenent of Haarlem, Netherlands, approved plans for several new churches in which freestanding altars “will be closer to the people instead of at the end of the apse, and so constructed that the priest can say Mass with the altar between himself and the people.”

By 1931, it was recorded in Orate Fratres that “many churches” in Europe, particularly Germany and Belgium, had removed the tabernacle from their altars and constructed Medieval-style “Sacrament Houses” or “Tabernacle Towers” near the sanctuary. With the tabernacle removed in this way, there was greater freedom and flexibility to utilize freestanding altars which faced the people.

Liturgically-focused textbooks from around the world confirmed the existence of this trend.

In the words of Father Gerald Ellard in his 1933 Christian Life and Worship, “[m]odern adaptations of the old table-altar are becoming common … bringing back the free-standing altar with the celebrant facing the people.”

Likewise Liturgia, published by the Chilean Federation of Catholic Girls’ Schools in 1935, rejoiced that while the Church had previously “almost abandon[ed] the beautiful, traditional, and simple table-shaped altars; nevertheless, thanks be to God, there is a tendency to return to the ancient form of altars.”

While a number of churches throughout Europe – and around the world – began to consider freestanding altars during these years, there seemed to be a particular interest in building or renovating cathedrals to follow this configuration.

Edwin Lutyens’s (eventually unrealized) 1933 plan for a new Catholic cathedral in Liverpool, England, included a massive freestanding versus populum high altar after the manner of the ancient Roman basilicas.

Monsignor Joaquim Nabuco, a renowned Brazilian master of ceremonies (and son of the famous Brazilian statesman of the same name) made an impassioned plea promoting this arrangement in a 1934 discourse addressed “to the Builder of a Cathedral” in the pages of Liturgical Arts, a journal dedicated to liturgical architecture and artwork:

“Would that architects and priests, laity and friars, monks and nuns, might once and for all understand that an altar is a table! People do not build dining room tables against walls; they place them in the middle of the room. [...]

“The proper place for the sacrificial table, if the church is built in the shape of a cross, is the centre of the crossing [the transept]. And if, in a cross-shaped church, one puts up a large and impressive cupola for pews and chairs, one will have committed a most grievous liturgical sin, a most unpardonable sin.

“If the altar cannot be put under the cupola, if, in other words, the centre of the architectural block is to be filled up with pews, then there must be no cupola. People sitting in the pews have no right to a cupola.”

Major Catholic congresses and festivals in Europe continued to celebrate Masses facing the people through the 1930s. One particularly notable example was the 1933 Vienna Katholikentag, where Archbishop of Vienna Cardinal Theodor Innitzer celebrated a vernacular German “Dialog Mass” for a crowd of 200,000 on a freestanding altar while facing the people at Schönbrunn Palace.

Vatican Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli’s versus populum Mass at Notre Dame Cathedral in 1937 was not even the most remarkable or high-profile example of this practice in France in that year.

The reason that Pacelli was visiting Paris in 1937 was on the occasion of the World’s Fair – the International Exposition of Art and Technology in Modern Life.

The 1937 Paris Expo was a particularly significant event for the Catholic Church. For the first time ever, the pope and the Vatican City State would be represented at the fair by a national pavilion like other countries. Even more than this, it was located in a prominent position, almost directly across the main boulevard from the pavilion of the Soviet Union.

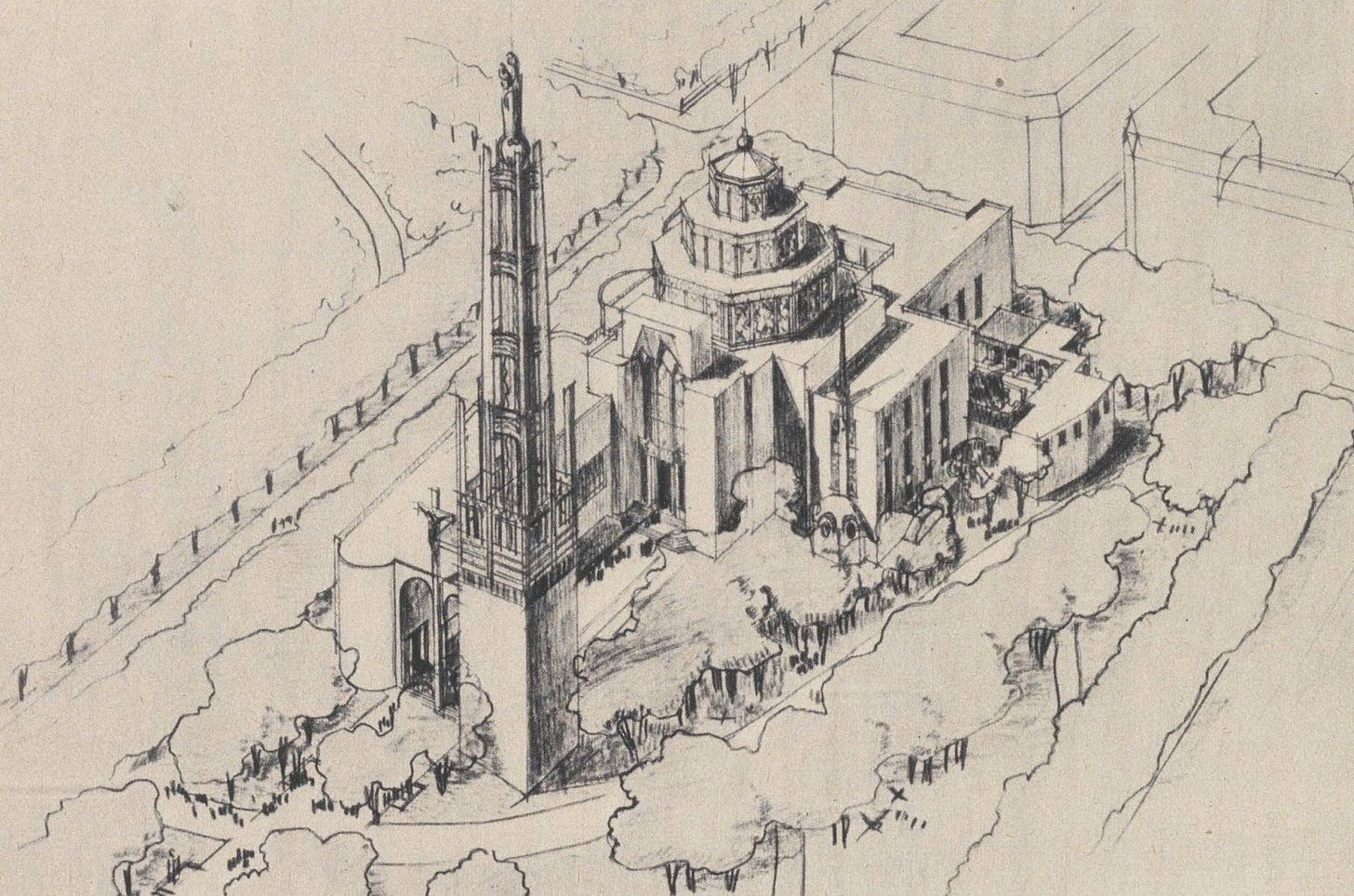

The renowned architect Paul Tournon was commissioned to design the papal pavilion. The church he created was a bold, triumphant, strikingly modern art deco structure.

Tournon reserved the design of the main church sanctuary for himself – the most daring and dramatic part of the entire pavilion.

It was octagonal in shape, with a massive freestanding high altar (called “the papal altar”) placed at the very center of the dome and surrounded on all sides by seating for the congregation. Overlooking the sanctuary was the papal throne, marked with the coat of arms of Pius XI.

This altar in many ways represented an ideal form of the modern freestanding arrangement promoted by the Liturgical Movement: plain and unencumbered and completely encircled by the congregation. The pavilion was meant to serve as the premier representation of the Vatican to the world – and a vision of the confident, modern Catholic Church in France.

The pavilion was visited by many thousands of people during the 1937 expo, and was used for many prominent Masses, including several celebrated by the Apostolic Nuncio to France Valerio Valeri.

The freestanding altar and versus populum trends would continue to grow in the 1940s and 1950s before ultimately blending together and converging during the implementation of the liturgical changes which followed the Second Vatican Council.

The nearly universal – and in many cases mandatory – changes to altars and liturgical orientation which followed Vatican II had a significant impact on the laity’s experience and understanding of the revised liturgy.

From the medieval to the modern age, Notre Dame has both reflected the architectural and liturgical trends of the wider Church and served as a unique exemplar and inspiration to others. It has been influenced by social changes and political revolutions, and has in turn shaped the styles and practices of other churches across Europe and throughout the world.

The contemporary debates about interior furnishings in Notre Dame are far from new. But they make it clear that the cathedral maintains the interest of both Christians and the public at large. More than eight centuries after its original construction, Our Lady’s cathedral continues to fascinate, impress, and inspire.

Finally, some coverage of the reality that the liturgical changes of V2 did not suddenly appear out of thin air in the 1960s, though it probably felt that way for many. The educational materials mentioned here also help explain how we had highly involved members of the laity who were ready to smash altars and whitewash the sanctuaries…all the “best” sources had been priming them for it over many years. The Liturgical Movement could also stand with another wave of critical (as opposed to hagiographical) scholarship while avoiding rad-trad excess. The roots of the good, the bad, and the ugly of post-conciliar liturgy go deeper than most people realize.

The debates over liturgy are worth having today, but without an understanding of the history provided here they will only generate heat, not light. Fassino has some a great service to us all with these articles.

As an aside, why the world look so beautiful before color photography? 😂