'To practice attentiveness, to nurture silence': How to read Pope Leo’s favorite book

'He worked in the kitchen, and made of it a place of prayer.'

In an interview earlier this month, Pope Leo XIV said he was recently asked which book, besides those written by St. Augustine, he would describe as most greatly shaping his spirituality.

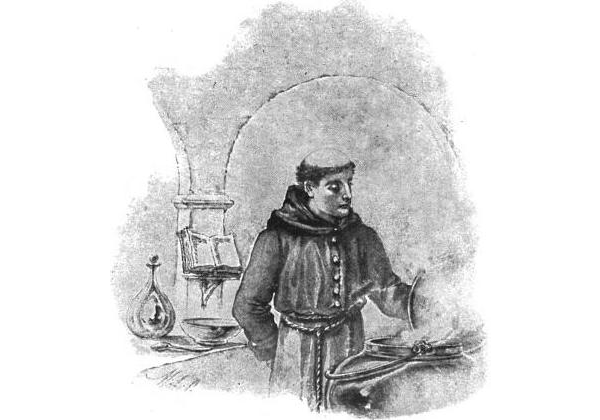

In response, the pope named the spiritual classic, “The Practice of the Presence of God,” by 17th-century Carmelite friar Brother Lawrence.