Wonder, the faith, and the brain

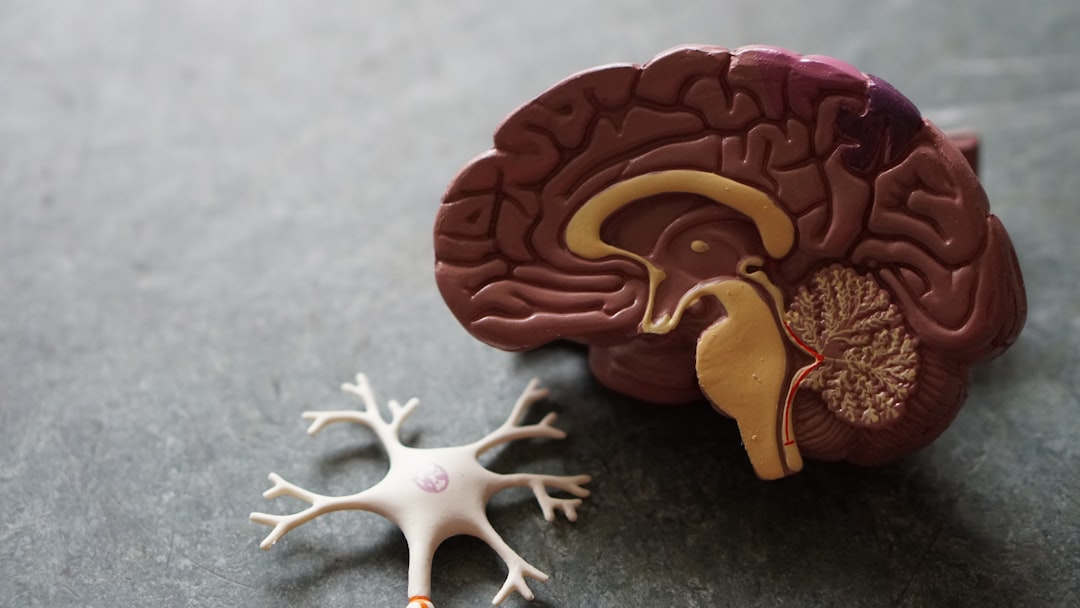

A Catholic neuroscientist on reality, and beauty, in the study of the human brain

It is not uncommon to find in the media grandiose headlines about neuroscience — among them the claim that brain researchers have proven free will is an illusion, that consciousness does not exist, or that the spiritual soul is unnecessary.

If those headlines paint an accurate picture of what neuroscientists actually do, how can a person …