Hey everybody,

Today is customarily the Feast of the Most Precious Blood of Jesus, kicking off the month of July, which is in the Church dedicated to the same.

There’s a whole interesting history to the feast, which was added to the Church’s universal calendar while Pope Pius IX was briefly in exile from the Vatican in the late 1840s, amid a period of revolutions across Europe that saw eventually the brief declaration of a republican government in the Papal States.

The feast was originally timed to coincide with the city of Rome’s liberation - by the French - from Italian republicans, and them return of ecclesiastical governance of the Papal States.

The pope only hung on to territory in Italy (apart from the Vatican City) for another 20 years, and only then propped up by the French, but the feast endured until revisions to the Roman calendar in 1969, when it was removed as universal commemoration, but remains observed in some religious communities, and as a feast of popular piety in a lot of places.

—

But that’s not what I want to tell you about today.

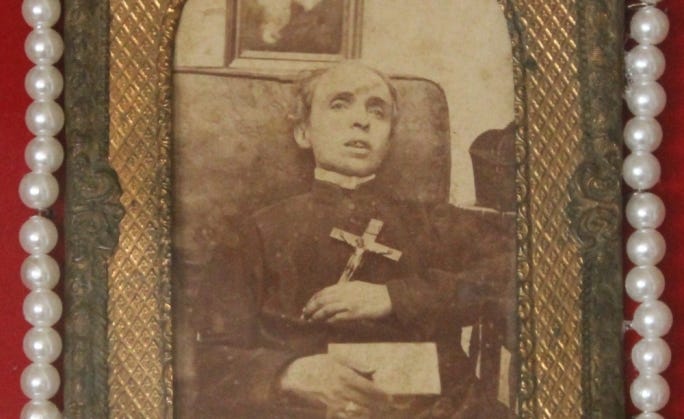

Because today is also the Church’s feast of a Maltese Catholic you’ve never heard of: Blessed Nazju Falzon.

Nazju was born in 1813 into a family of lawyers — his dad was a lawyer who became a judge, and his mom was the daughter of a lawyer who became a judge.

There were four Falzon boys in the family — Nazju, Anthony, Calcedonio, and Francesco, and they all became lawyers.

Anthony married and went into practice, while Calcedonio, Francesco, and Nazju entered seminary after law school. But while his brothers were ordained, Nazju decided against it, shortly before his scheduled diaconal ordination.

Nazju had excelled in study. He was well-liked, a good (practice) preacher, he was funny and friendly. He was devout and serious about the faith.

But for reasons known only to him and to the Lord, Nazju decided, just before ordination, that he was unworthy of priesthood.

He left seminary, moved to his family’s villa, and entered a period of prayer and penance. People were mystified. The Bishop of Malta didn’t get it. No one quite got it. But Nazju had decided his vocation lay elsewhere.

So he became something of an ascetic. He fasted every other other day. He’d received minor orders, and was entitled to continue wearing the cassock, so he did. He went to daily Mass, he gave away money from the family’s accounts, he spent hours each day in the family chapel.

Soon God was calling him to an apostolic life. Nazju started teaching religious instruction, mostly to children at the parish, and then to adults who asked him for catechesis. He taught Latin, Italian, and English lessons, for free, to little classes in his house.

He wrote devotional books in simple language for families to pray with. He translated spiritual books into the Maltese language. And while he never set up a law practice, he started giving people bits of legal advice, or helping them with small cases.

But God was calling him to more. When Nazju was alive, Malta was a British crown colony. It was also something of a way station for the British Navy. There were British sailors, marines, and soldiers everywhere — 20,000 of them stationed in Malta. Few of them excelled in piety.

But Nazju wanted to give them the Lord. So he started hanging around bases, and then the bars that the military frequented, and talking with them about the Lord. He’d meet British officers or enlisted sailors while practicing his English, and he’d invite them to catechesis, or to prayer services — first at his house, and then at parishes, when his own living room wasn’t big enough.

He organized other lay people to do the same, a network of evangelizers and catechists, who saw in the British military occupation of their island a mission field.

Nazju became an evangelist of the British navy in Malta. In fact, he moved to Valletta, Malta’s capital, to be more available to that work.

He founded a group for British sailors called the Congregation of the Rosary. They called it “The Congregation.”

Surprisingly, it was effective.

He also became a trusted confidante, and he let sailors deployed across the Mediterranean keep their things in storage at his house — with promises to send letters or packages home to their families if they were killed.

Huge groups gathered at the Jesuit parish in the city, where Nazju taught them the faith in English. He had a reputation for extraordinary holiness.

More than 650 sailors and soldiers were baptized or received into the Church because of his influence.

Along the way, he became a secular Franciscan.

But when he was 52, Nazju had a heart attack and died.

While his cause began in Malta, it was British bishops who urged the pope most strenuously to beatify him; his legacy in their country endures after more than a century.

He is to me a mystery. Why didn’t he continue to ordination? Why didn’t he practice law? What was his interior life?

I really don’t know. But I know that God moved in Nazju Falzon’s life, and that his faith bore fruit.

May he intercede for us.

The news

This is serious, well-sourced investigative journalism — the kind The Pillar does best. It’s also a major test for Pope Leo XIV, coming in Peru, the country in which he served as a bishop.

The story of Catholic MP Chris Coghlan, who voted in favor of Britain’s assisted suicide bill, went viral this weekend, after Coghlan’s parish priest told the lawmaker that his vote for assisted suicide meant he could not receive the Eucharist.

Coghlan claims that the bishop of his diocese has assured him that “it is not the Church’s position to deny Holy Communion over this.”

But the bishop has not actually spoken publicly.

And to untangle the whole situation — and separate fact from fiction — there’s no one better than our own Luke Coppen.

It’s ironic, I guess, that the pope who has set himself up to address AI is now being targeted by AI fakes.

But here’s how to spot a fake Pope Leo.

So what American beati might be soon up for canonization?

—

In our Pillar columns, Bronwen McShea’s got the story of the Carmelite Martyrs of Compiègne.

“They gave me food, clothes, and helped me with rent and stuff like that, which is great,”one participant told The Pillar.

“But what was even more helpful is they gave me a safe place to talk whenever I needed something. I always know that I can come on in and I will be treated with respect, as a person, and they will figure out a way to help me.”

—

I’ve got one more thing to tell you about, but first, please let me invite you to come on The Pillar’s pilgrimage to Rome this Advent, hosted by me and Ed.

It’s the Jubilee Year, so we’ll go through the Holy Doors to obtain a jubilee plenary indulgence. We’ll also hit some of the sites most important to Pope Leo XIV, and we’ll make it a point to see the pope.

We’ll do the Vatican Museums, Roman trattorias, and my favorite restaurant in Trastevere. We’ll have Mass, opportunity for confession, and gelato.

But it’s a Pillar Pilgrimage, so we’ll also record a Pillar Podcast, see some nerdy stuff most people don’t, debate vigorously, drink well, and visit some of our Roman bars and pubs.

In short, it’s going to be a blast, and we still have a few spots, and I hope you’ll come.

The fake is really fake

A friend sent me over the weekend a social media ad for an AI sermon writing tool, SermonAI, which promises to “revolutionize sermon prep by offering pastors a side-by-side research and writing platform, akin to having a savant in biblical history, theology, original languages, and culture right beside you.”

SermonAI says it doesn’t write a sermon for you, that’s it’s a “research assistant” — but anyone who has ever employed a research assistant knows that the point is to get drafts that you can polish up a little bit and then call your own.

The video demonstration makes pretty clear that SermonAI is a generative chat program which “instantly integrates into your sermon” the material which HotCiti LLC generously calls “your research” — the fruit of your asking questions of the AI chatbot, and it giving you multi-point answers, including color glossy photographs with circles and arrows and paragraphs explaining each one.

Now the obvious problem with this is that AI tends to get things wrong and make things up, leading to the prospect that, like Quentin Tarantino, you’ll end up building a whole universe around a fake Bible verse.

But the “Ezekiel 25:17 problem” isn’t the biggest issue with SermonAI — not by a long shot.