Pillar subscribers can listen to this Pillar Post here: The Pillar TL;DR

Hey everybody,

It’s June, and you’re reading The Tuesday Pillar Post.

Later, I’ll have some things to say about liturgy, the new breviary translation, and papal baseball cards. But first, a remarkable story:

Pope Leo XIV was ordained an Augustinian priest in June 1982, seemingly beginning a path of God’s Providence that led to his now extraordinary ministry in the life of the Church.

But today I want to tell you about another Augustinian priest, a man called to a priesthood as extraordinary as any pope. I want to tell you about Fr. Bill Atkinson.

Bill, as his friends call him, was ordained in 1974, eight years before the pontiff. He was born in 1946, went to an Augustinian high school outside Philadelphia, and in 1963, began formation as an Augustinian postulant.

In February 1965, Bill was a novice in upstate New York. There was a surprise snow storm on February 22, so Bill and his fellow novices put their boots on, grabbed the novitiate’s toboggans, and climbed a sledding hill on the novitiate grounds.

The guys had a great time out in the snow, until the accident. But on a run down the hill, Bill’s toboggan hit a tree. The impact tossed him into the air, and then into the ground.

Bill’s neck was broken. His spinal cord was severely damaged. Few expected him to live more than a few weeks.

By March 1, as he lay in the hospital, he was widely expected to die. From his bed, he was permitted to profess the evangelical counsels, the vows of Augustinian religious life.

His brothers were told to pray that he’d have a good death.

But Bill lived. He would be paralyzed from the neck down, quadriplegic, unable to walk, and with limited use of his arms. But he was an Augustinian. He perdured in religious life. He believed that God was calling him to priesthood — despite the canonical irregularities which prevented him from holy orders.

When he left the hospital, he continued in studies and formation. The Augustinians allowed him to continue in seminary, uncertain of whether he’d be ordained, and advised by the Apostolic See that a dispensation was unlikely.

His formation was slowgoing. He needed help with every part of his daily life, including his studies.

In 1972, when the Augustinians asked for a dispensation from the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life, they were told that Bill should write personally to the pope.

“From my physical condition,” the young man wrote to Paul VI, “the Lord is obviously calling me to a very special vocation, closely conformed to his own cross.”

“It is my conviction that in this modern age, where the dignity of human life is measured by productivity alone, and where suffering should be eliminated at all costs, we must more than ever preach Christ crucified.”

“I believe that my own witness to the world of the mysterious love of God, working in my weakness, can be of tremendous assistance to those people who lack faith, who lack hope of a better tomorrow because they see and feel the despair of the day’s routine — who are themselves called to suffer in some special way.”

“Let it not be my will, but his that is done.”

The pontiff saw in Bill a man worthy of priesthood. He granted the dispensation.

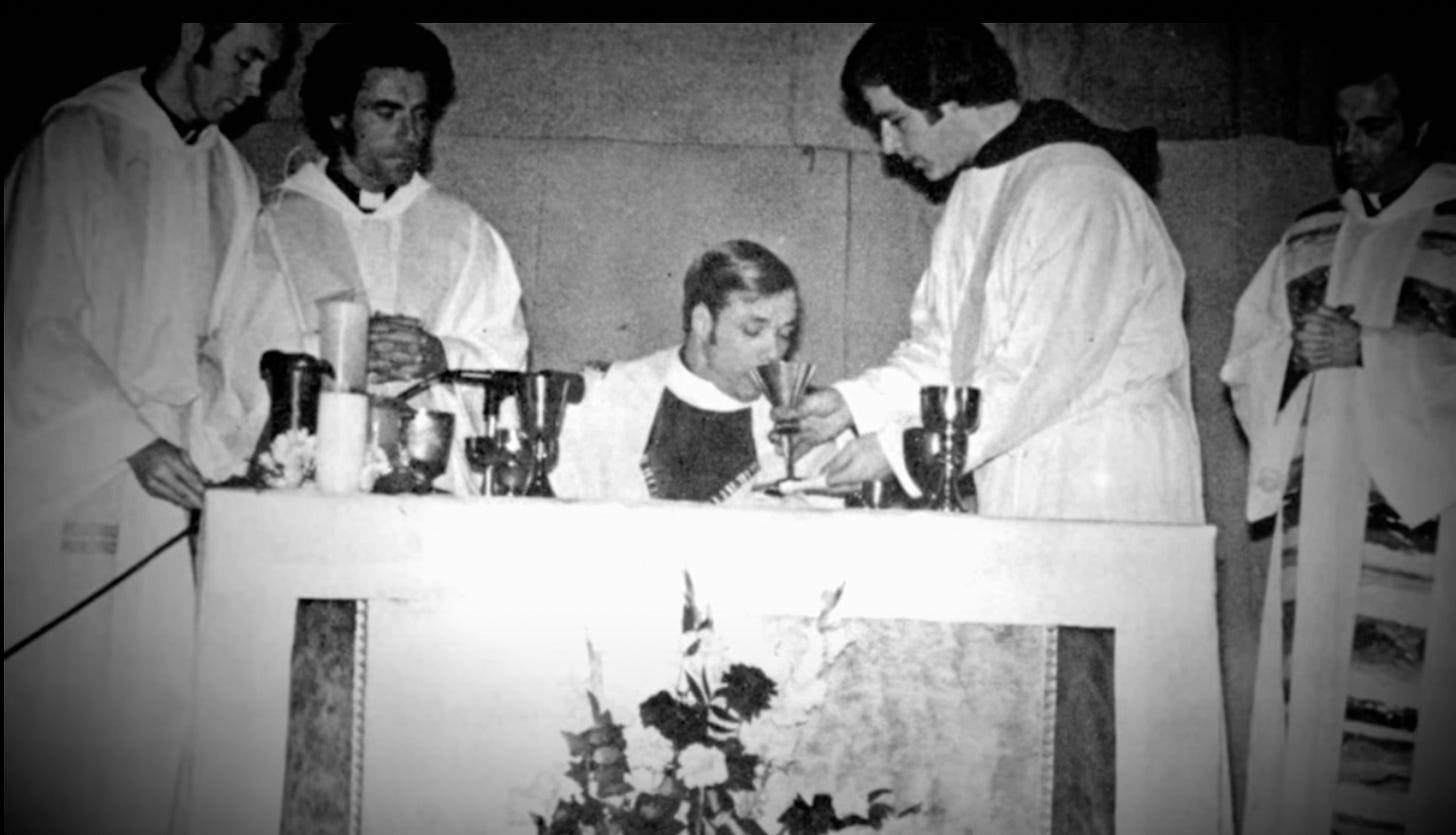

And the next February, Bill was ordained a priest of Jesus Christ — the first quadriplegic man to be ordained.

He needed help to offer Holy Mass. He needed help, of course, even to go to the bathroom or change his clothes. But he accepted that help, with humility, in service to his sense of a vocation.

He said that in being cared for, he experienced “the Father’s love, turning a stumbling block into a stepping stone.”

Fr. Bill spent the next 30 years teaching high school, and immersing himself in the life of Msgr. Bonner High School, his own alma mater.

As his students got older, he did a lot of weddings. He spent hundreds of hours in the confessional. He was beloved, and he was known to be quite funny.

Until 2004, he taught every day, until his health no longer allowed it, and he was moved to nursing care. On September 15, 2006, Bill died, surrounded by his fellow friars, and his family.

In 2017, Archbishop Charles Chaput of Philadelphia opened the cause for the prospect of Bill’s canonization. His cause remains open.

And in God’s Providence, Pope Leo may someday have occasion to declare his confrere a saint — to raise his brother Augustinian to the altar.

Become a True Leader with an MBA from the University of Mary. Gain the confidence of an executive, the insight of a specialist, and the integrity to be a champion for the Common Good. Pillar paid subscribers receive an exclusive $10,000 scholarship - Apply today!

The news

On Friday, Cardinal Eijk — a self-described “Pillar reader, in a good way” — talked with The Pillar about the Pontifical Academy for Life and the John Paul II Institute in Rome — both, until recently, headed by the controversial Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia.

Eijk told The Pillar that “it is very important that we try to reestablish unity in the Church. And that needs to come from a proclamation of the faith that is clear and unambiguous. And that should also happen in the field of morality and ethics.”

“When the pope is clear and unambiguous in proclaiming this part of the doctrine, that will be very helpful for people to rediscover the truth. And they should be helped in doing so,” he added.

The cardinal also talked about the growth of the Church in the Netherlands, new ethical challenges for the world, and the enduring importance of Evangelium vitae.

This is an interview you want to read.

—

An Orthodox monastery has been in the news this week, after rumors circulated on social media that the Egyptian judiciary had ordered St. Catherine’s Monastery closed, along with the eviction of one of the oldest monastic communities in the world.

But the situation is much more complicated than what you’ll read on social media. And when I want the straight scoop on complicated stories like this, I call in Luke Coppen.

So here’s the Egyptian monastery fracas, explained.

The topic is relevant one — in eastern Europe, in the middle east, in the Chinese claims to fishing rights in the Pacific, and around the world.

What does AI mean for warfare? What happens when things go wrong? What does any of this mean for humanity?

This is not an abstract conversation — it’s about what’s happening, right now, and what the Gospel has to say about it.

A long time ago, Pope Innocent II attempted to ban the crossbow — what hath that to do with robots and modern war crimes?

—

After national attention to restrictions on the Extraordinary Form of the Mass in Charlotte, North Carolina, The Pillar’s journalism intern Jack Figge talked with young Catholics in Charlotte to find out what the Traditional Latin Mass has meant to them — and what they plan to do now.

Some say they’ll start attending the Mass at the designated chapel outside of Charlotte. Others say they’re torn between their parish community, and the liturgical form in which they’ve found Christ.

And many said that as they grapple with a difficult situation, they’re aiming to put their sadness on the cross of Jesus Christ.

Here’s what young Catholics in Charlotte have to say.

And for a little more on the topic, here’s an analysis I wrote on the challenges faced by Charlotte’s bishop after a very difficult first year for the diocese.

The priest has since been accused of “boundary violations” in each of the parishes where he’s served. And Pennsylvania police have told the diocese that the abuse allegations were “credible,” but that charges couldn’t be filed because of the criminal statute of limitations.

There will be no criminal prosecution, because of that statute of limitations. Because the alleged abuse allegedly happened before the priest was a cleric, it doesn’t constitute a canonical delict. And yet, there are serious allegations — judged to have the semblance of truth — and a history of impropriety during priesthood.

Charlotte is not the first diocese to face that circumstance, and the story points to a challenging situation for any diocese — but one that the Church faces with increased regularity.

The priest is not being laicized, and the diocese does have to figure out what to do with him next. There is no conviction, but there is no right to ministry in the Church either. Others have judged that returning such a man to ordinary ministry, given the pattern of allegations, is imprudent, at the very least. But there is seemingly a lacuna in the law here, at least in my view. So in Charlotte, the bishop has said his priest’s future ministry in the diocese will depend, in part, on his completion of an “assessment and training” program.

And from our Pillar columns section, two offerings for you:

Stephen White on “what the bishops never sees” when it comes to liturgy.

AND

Daniel Lipinski on “The Blues Brothers” and “old-time Catholicism.”

Now, I have a confession to make about that one. I’ve never seen “The Blues Brothers,” I have a reflexive aversion to the hype around it, and I have always found Dan Akroyd to be the only insufferable “Ghostbuster.”

In fact — and I know I’m going to get roasted here — I’m not sure Dan Akroyd has ever made me laugh. When he’s in something, and the scene’s on him, I’m usually waiting around for Akroyd’s much funnier contemporaries to do something funny.

I couldn’t abide “Coneheads.” (Could anyone?)

Plus, I’m not sure I agree with Lipinski’s rosy vision of institutional Chicago cultural Catholicism, even if it did (seemingly) contribute to the formation of a pope.

But on the other hand, Lipinski’s column (kind of) accuses The Pillar’s Ed Condon of “an affluent, sheltered, north suburban view of [Chicago],” and — by golly — that made me laugh.

Become a True Leader with an MBA from the University of Mary. Gain the confidence of an executive, the insight of a specialist, and the integrity to be a champion for the Common Good. Pillar paid subscribers receive an exclusive $10,000 scholarship - Apply today!

The pastoral challenge

Before I give you a breviary update, let me tell you a story.

A few months ago, I was on a college campus for Mass, at a university well known for the active faith and devotional life of its students.

At a large university Mass, I found myself intrigued when the Extraordinary Ministers of Holy Communion made their way to the sanctuary, by one student in particular.

She was wearing a mantilla, to veil, in the manner of many Catholic traditionalists. As the music played, she was also waving her arms above her head to pray, in the manner of many Catholic charismatics. When the Eucharist was distributed, she knelt to receive on the tongue. Then she stood, took the ciborium in her hand, and distributed Holy Communion to other students.

It was a charismatic-traditionalist mashup that I found intriguing. And so curious was I that I got into her line for the Eucharist. And sure enough, before she put the host on my tongue, she said “Corpus Christi” instead of “Body of Christ.”

It was pious chaotic discordance. A little from every cupboard. And it was totally beautiful, in my view. This student was appropriating practices she had found beautiful, and was doing so out of real faith. I loved it.

And I was very glad that no one had pulled her aside and told her to pick a lane, so to speak.

Why do I point that out?

Well, because of the discussion about Charlotte, North Carolina, to be honest. Here’s what I mean.