Hey everybody,

It’s the feast of St. Sebastian, and you’re reading The Tuesday Pillar Post.

I’ll get to St. Sebastian later — kind of — but I’ve been thinking about a different Christian this morning.

Hans Egede was born in January 1686, and baptized a Lutheran, possibly at a medieval stone church at Trondenes, Norway, or in another nearby local parish church.

Don’t hold it against him that Hans was baptized a Lutheran — he was only an infant, you see, plus, his grandfather was a Lutheran cleric and his uncle was too. And Hans lived about 150 miles north of the Arctic Circle, in the little town of Harstad, where everybody was a Lutheran, and where he’d probably heard precious little about the fullness of the divine and Catholic faith.

Young Hans had a beautiful imagination, he loved history, and he had a sense of adventure. So after university in Copenhagen, he was ordained a Lutheran priest and took up ministry in little parishes in the remote island villages of northern Norway.

He married — Lutheran prelates will do that, you know — and had four children.

But while his life was idyllic service to the Gospel, his vision and mind were far afield. See, when Hans was a boy, he read stories about the Norsemen who had arrived, hundreds of years before, on the big glacial island of Greenland, a sheet of ice plunked down between the frigid waters of the Arctic Ocean, and the rough seas of the North Atlantic.

By the time Hans was a boy, it had been hundreds of years since anyone had heard from the Norse settlers of Greenland.

But Hans thought about them constantly. He wondered if their descendants were still living in Greenland, and most of all, he wondered if they had retained the Christian faith, in centuries without contact.

Hans wanted to go to Greenland and proclaim the Gospel. When he was a boy, people admired his zeal. When he was an adult, and the dream persisted, his family and friends thought it was insane — that’d he land on a sheet of ice and be dead within a year. His wife discouraged him. Everyone thought a foray into Greenland was crazy.

So Hans told his wife they should give the matter to God. They should both pray about it, until the Lord was clear about what he wanted.

And soon, something totally unexpected happened. Gertrud — Hans’ wife — said she felt called in prayer to trust him. She soon promised him to follow wherever the Gospel took him.

Eventually, he asked King Frederick IV of Denmark-Norway whether he could go to Greenland, and start a mission there — effectively restoring the kingdom’s colonial claim to the island.

Frederick agreed.

But the trip couldn’t just be him and Grutud, carrying a Bible and hoping for the best. To make it work, they’d have to follow the colonial pattern, the king and his advisers made clear. They’d need money and ships and supplies.

So Hans founded the Bergen Greenland Company, gathered investors, and secured permission from his king to govern Greenland, to raise a military force, to collect taxes and run courts. Before setting foot on it, Hans was effectively the governor of Greenland, at least in Europe’s view.

Now, not every investor was motivated, as Hans was, by the Gospel. Most of the people who gave him money for Greenland were merchants who wanted mineral rights on Greenland, or to trade for whale blubber and furs. Hans’ missionary endeavor was tucked into a commercial enterprise, with him, in principle at least, at the helm.

On July 3, 1721, Hans and three boats landed on Hope Island, on Greenland’s west coast. They claimed the land as Hope Colony.

But most people couldn’t hack it. The settlers were cold, they were miserable, and they started getting scurvy. So within a year, most people went home. Hans and his family stayed. They trekked along the coast to look for survivors of the ancient Norse colonists. They found none.

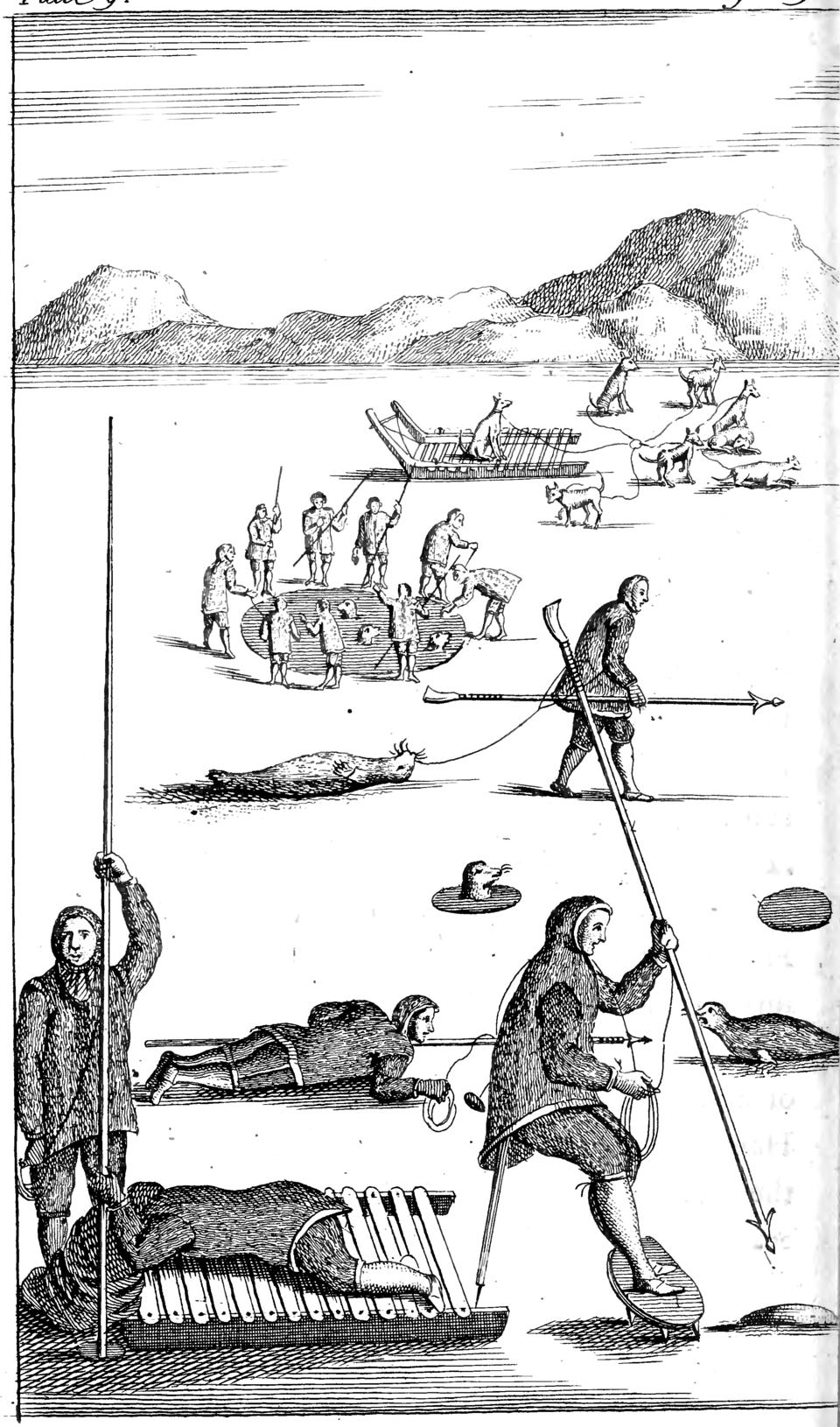

So the settlers did two things. They started whaling, and they started preaching to the Inuit people.

The whaling didn’t work. Dutch whalers who worked the Greenlandic coast burnt their whaling station to the ice.

The preaching worked better. By 1724, Hans was baptizing Inuit converts. Ships and supplies arrived, and Hans built a little chapel.

But scurvy was the downfall of nearly everyone. More settlers died of it.

By 1729, Hans and his family were nearly the only Europeans living on Greenland. They kept preaching. They fought frostbite and hunger. They lived for a while in leather tents that stunk, and did little to protect them from weather. They learned the Inuit language, and very slowly built relationships.

But Hans also had to deal with the remaining colonists who had come from Norway, many of whom grumbled and complained, fought with each other, and frequently fell ill.

When smallpox came to Greenland through a trading vessel, it was devastating to Europeans and Inuit alike. Hans spent months burying the dead and ministering to the sick. Whatever else that did, it brought him better relationships with the Inuit people, and led to growth of his small Inuit Christian community.

Eventually more missionaries came, and one of their mission stations became the city of Nuuk, today Greenland’s capital.

Hans continued to preach, to live and minister to the Inuit, and to hope that he might find the lost Norse settlers of old. The closest he came were some building foundations believed to be Norse. His sons — especially Paul — joined in the work; Paul would eventually work with an Inuit woman, Arnarsaq, to translate the New Testament into Greenlandic.

But in 1735, Gertrud contracted smallpox. She died. Hans took his wife’s body to Denmark to be buried.

Before he left, he preached a farewell sermon, telling the people that he had come for the glory of God, and that they might know the Gospel.

In Copenhagen, he became rector of a small seminary training more pastors for mission in Greenland. He oversaw the production of a catechism for use there. He did not return. But he died remembered as the “Apostle of Greenland.”

—

Today Hans is controversial in Greenland — not so much for what he did, but for what he represents: the long-term colonization his mission is seen to have begun, the erosion of Greenlandic Inuit autonomy, a loss of Inuit culture and tradition in the centuries thereafter.

From what I’ve read, Hans was singularly focused on the proclamation of the Kingdom. I don’t know what he would have thought about the controversy over him — or even what his presence in Greenland occasioned.

I also don’t know what Hans would have thought about the bigger controversy surrounding today his beloved Greenland. I know that it was important to him to clarify that his intentions in the country were not “temporal benefit and gain” but only the salvation of souls. He took that seriously, especially after Gertrud placed her trust in him.

If he’s in purgatory, we should pray for his soul, and for the souls of the Greenlandic Christians who followed him. If he’s in eternal happiness today, we should hope he is interceding for his country.

In any case, here’s the news.

The news

We talked with Bishop Andrew Cozzens about that data. Here’s what he said:

“Even as we look at the data from this impact study, we have to remember that you can’t really measure revival — you can’t measure what the Holy Spirit’s doing.

For example, who [in the early Church] could have predicted the conversion of the Roman Empire? You can’t predict the work of the Holy Spirit, but you can learn from what people say. And in this way, [the survey] is a kind of an action of synodality, to listen to people.

…

One of the good news things that surprised me was that people who attended one of our national events, whether a pilgrimage or the Congress itself, said they were 50% more likely to do some kind of outreach in their faith life after attending those events.

That’s huge.

We’ve been trying to work on missionary conversion in the Church in the United States for years. Of those who attended, many said they experienced a missionary conversion. Many said they were more ready now to share their faith, they were ready to live a Eucharistic life, and 60% said they have done more evangelization activities since the beginning of the revival.”

The dicastery — which is well-known to be understaffed and overworked these days — has proposed a rethink on the processing of these kinds of laicizations.

Now, for canon lawyers, this is of immediate interest, especially given recently discussed lengthy turnaround times at Clergy.

But for everybody, what’s the takeaway? Well, if you ask me, it’s this: It’s been more than 40 years since we’ve had a canonist pope, and now we do. The pontiff is going to give a careful review to known pressure points in the Church’s administrative and juridic apparatuses, and that may prove to make the Roman Curia much better tooled to serve the universal Church.

We shall see.

Ready to get out of debt, save for emergencies, morally invest, and give generously? Claim your 2-week extended free trial at CatholicMoneyAcademy.com/pillar and learn how to practically manage money with virtue. Sign up by January 31 for a chance to win $100.

I don’t know what you know about Alcoholics Anonymous, but you might not know about its early Catholic connections.

Here’s an interesting report about exactly that.

—

It is not clear exactly why Bishop Paskalis Bruno Syukur, O.F.M has resigned from his post, seemingly at the direction of Pope Leo, but the bishop said that it was for him a “spiritual transition” that came through obedience to the Vatican.

Bishop Syukur came to global prominence on Oct. 6, 2024, when Pope Francis announced that he would be among 21 new cardinals created in December that year. But the Vatican said later that month that Syukur had asked not to be created a cardinal.

It is a highly unusual situation, suggesting decisive action on the part of Leo XIV.

—

The bishop has said that reassignment comes with support of the diocesan lay review board, and that the priest has completed required steps to “meet the standards” required for priestly ministry in the Charlotte diocese.

But the case could point to a gap in the Church’s canonical norms for clerics accused of abuse before ordination, and towards ambiguity about the status of some accused clerics. It could also point to the difficulty posed by differing uses of the term “credible” to characterize allegations of abuse.

And the whole thing is unfolding in a diocese already embroiled in division over the leadership of Bishop Michael Martin.

Because Broglio is the archbishop of the military services — and because he is not the type known to mince words — his comments on our international affairs might be seen to carry some real weight.

Though he’s not the only American churchman to weigh in our current status rerum.

In a joint statement released Jan. 19, three U.S. cardinals — Tobin, Cupich, McElroy — warned that “[T]he United States has entered into the most profound and searing debate about the moral foundation for America’s actions in the world since the end of the Cold War.”

It is worth noting that at present, Tobin, Cupich, and McElroy are the only cardinals serving as sitting U.S. diocesan bishops — Dolan is an apostolic administrator on his way to retirement, and Gregory, DiNardo, Burke, and O’Malley are already there.

The three cardinals’ statement was broader than Greenland, calling for a “moral foreign policy” by “renounc[ing] war as an instrument for narrow national interests, and “seek[ing] a foreign policy that respects and advances the right to human life, religious liberty, and the enhancement of human dignity throughout the world, especially through economic assistance.”

It was, in short, a broadside against the foreign policy priorities which have come to be called colloquially the “Donroe Doctrine,” both in terms of interventionism and the significantly reduced American foreign aid of the last year — the dismantling of USAID now fallen from American headlines, but having genuine ongoing effect around the world.

You can read about the statements here.

I have been interested in the reactions to both statements of the past 24 hours.

My texts and my social media feeds have been flooded with people criticizing the cardinals’ statement as insufficiently inclusive — not multilateral enough, as it were — because it was not enacted through the U.S. bishops’ conference or because it did not include as signatories cardinals from the other side of the ecclesiastical aisle.

Those criticisms have come even from people who say they agree with the substance of what the cardinals said, but don’t like the form in which the message was delivered.

I’m not sure those criticisms should carry much weight. Again, Tobin, Cupich, and McElroy are, at the moment, the American cardinals leading dioceses, and it seems perfectly reasonable that a nation’s active cardinals might band together to say something. It’s also plausible that they floated the statement to other cardinals, and didn’t get any bites.

The criticism proves what I’ll call the “Blase rule” of American ecclesiastical life — that anything involving Chicago’s cardinal will be judged not by what he’s said, but the fact that he’s the one doing the saying.

Now, you might be asking yourself if the Blase rule is the inverse ecclesiastical analogue to the supposed TDS, or Trump Derangement Syndrome, which is diagnosed so frequently in social media conversations among distantly connected interlocutors on places like Facebook.

That’s a matter for your private judgment, and I dare not offer you my own view on whether the “Orange Man Bad” phenomenon — if it exists — has a direct episcopal parallel in the Blase rule.

But I will say that at this point, the cardinal archbishop of Chicago could stand in the street to recite the creed, and still be met by a chorus of skepticism. And, if you ask me, the cardinal’s limited moral authority — as distinct from his actual episcopal and official authority, which should always be obeyed and respected — is the fruit of his choices about how to approach the public square, which have done little to command rapt attention from practicing American Catholics.

So it is what it is.

But this week I have found even more interesting online the presumption that Broglio, speaking as he is about Greenland, must be some kind of excessively liberal bishop himself.

It’s a startling accusation to throw at a man whose election to the USCCB presidency caused the National Catholic Reporter to collapse into a heap of quivering vapors.

But that’s the state of our Catholic American polis at the moment: Episcopal statements are filtered through our political priors to assess their supposed orthodoxy — if we agree with them, great, and if not, they must have been issued straight from the mouth of a bogeyman so liberal or conservative as to warrant immediate dismissal.

In that context, I find myself wondering whether the teaching office of the episcopate is actually positioned to teach: Can bishops teach Catholics to think like Catholics, if the presumption is that we’ve already learned to do so by the tribal partisan alliances to which we’ve sworn?

I’d like to hope the answer is yes.

But that very question — how to assess and consider social and moral issues from the lens of the deposit of faith — is going to require something very different from what the Church usually presumes about her teaching documents, namely that they will be received in good faith by the Catholics they’re intended for, just because they come from her sacred pastors.

And that brings me back to the interview we did this week about the National Eucharistic Congress. Because just teaching isn’t working for the bishops right now, in my view.

And if that’s so, maybe Paul VI was right: “Modern man listens more willingly to witnesses than to teachers, and if he does listen to teachers, it is because they are witnesses.”

The Eucharistic Congress was the witness of bishops on their knees among their fellow Catholics, before the Eucharistic Lord, looking for the truth in the very person of Truth.

And that matters. You can’t think like a Catholic if you’re not living like one, praying like one, and trying to see the world as Christ does. Everything else comes after that.

I suspect before teaching documents will be especially effective to actually change or form minds, much more of that witness will be necessary.

Sheets of ice

Ahead of St. Sebastian’s feast — he being patron of athletes and athletics — this weekend played out for our household in keys of high athletic drama.

We watched my son Daniel’s basketball team stave off tournament elimination, even while he came home with a jammed and swollen finger that could see him sit the next playoff game.

We watched our Denver Broncos escape playoff elimination, and then learned that Bo Nix — our always unlikely hero — will need screws in his ankle, and be replaced in the playoffs by a man using the surname Jarret as a given name, and spelling it with an improbable number of t’s.

And we watched, like all of America did, this particular glitch-in-the-matrix moment, and the crushing defeat which came after it.

With playoff football giving intense drama and wonderment, I think Americans can be forgiven for forgetting that the 25th Winter Olympiad will begin early next month in Milan.

In fact, it’s no big deal that Americans don’t remember the Olympics until they begin. We’ll remember when the games come on, and we all spend a few weeks pretending to be experts in skiskyting, or winter biathlon.

But it’s a bigger thing that the Italians forgot the Games were coming. And in an improbable turn of events, that could be really important for Greenland.